The earliest modern humans in Europe mastered bow-and-arrow technology 54,000 years ago

Based on research in France’s Mandrin cave, in February 2022 we published a study in the journal Science Advances that pushed back the earliest evidence of the arrival of the first Homo sapiens in Europe to 54,000 years ago – 11 millennia earlier than had been previously established.

In the study, we described nine fossil teeth excavated from all the archeological layers in the cave. Eight were determined to be from Neanderthals, but one from one of the middle layers belonged to a paleolithic Homo sapiens. Based on this and other data, we determined that these early Homo sapiens of Europe were later replaced by Neanderthal populations.

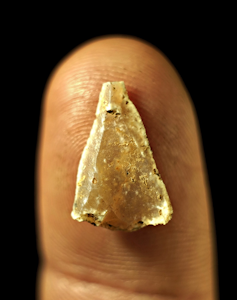

The single Homo sapiens tooth was discovered in a remarkable and rich archeological layer that also included approximately 1,500 tiny stone blades or bladelets – some were less than 1 centimeter in length. They were all part of the “Neronian” tradition, named in 2004 by one of us, Ludovic Slimak, after the Néron cave in France’s Ardèche region. Neronian stone tools are distinctive and there were no similar points found in the layers left behind by the Neanderthals who inhabited the rock shelter before and after. They also bear striking parallels with those made by other Homo sapiens along the east Mediterranean coast, as exemplified at the site of Ksar Akil northeast of Beirut.

This month in the journal Science Advances, we published a study announcing that the humans who arrived in Europe some 54,000 years ago had mastered the use of bows and arrows. This discovery pushes back the origin in Eurasia of these remarkable technologies by approximately 40,000 years.

The emergence in prehistory of mechanically propelled weapons – spears or arrows sent on their way by throwing sticks (atlatl) or bows – is commonly perceived as one of the hallmarks of the advance of modern human populations into the European continent. However, the origin of archery has always been archeologically difficult to trace because the materials used tend to disappear from the fossil record.

Archaeological invisibility

Armatures – hard points made of stone, horn or bone – constitute the main evidence of weapon technologies in the European Paleolithic. Materials associated with archery – wood, fibres, leather, resins, and sinew – are perishable, however, and so are rarely preserved. This makes archaeological recognition of these technologies difficult.

Partially preserved archery equipment was found in Eurasia only in more recent times, between 10 and 12 millennia ago, and in frozen ground or peat bogs, as at the Stellmoor site in Germany. Based on the analysis of armatures, archery is now well documented in Africa approximately 70,000 years ago. While some flint or deer-antler armatures suggest the existence of archery from the early phases of the Upper Paleolithic in Europe more than 35,000 years ago, their shape and how they were hafted – attached to a shaft or handle – do not allow confirmation that they were propelled by a bow.

More recent armatures from the European Upper Paleolithic bear similarities to each other, not allowing us to clearly determine whether they were propelled by a bow or an atlatl. This makes the possible existence of archery during the European Upper Paleolithic archeologically plausible, but difficult to establish.

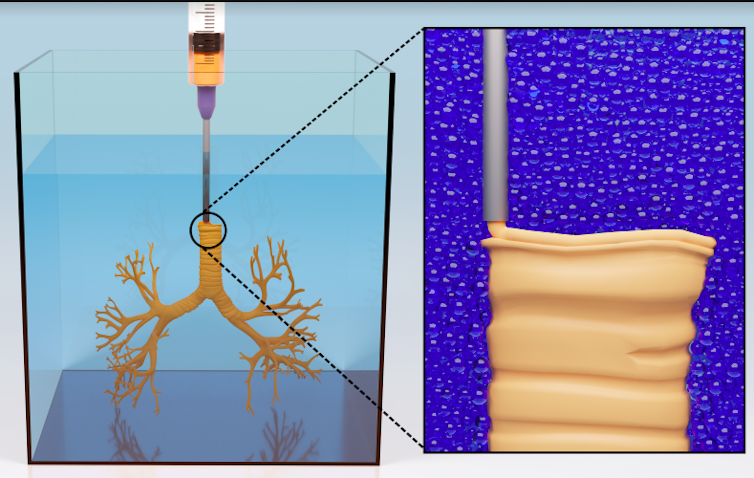

Experimental replicas

The stone points found in the Mandrin cave are both extremely light (30% weigh hardly more than a few grams) and small (almost 40% of these tiny points present a maximum width of 10mm).

To determine how they could have been propelled, the first step was to make experimental replicas. We then hafted the newly made points into shafts and tested how they behaved when shot with bows and spear-throwers, or by simply thrusting them. This allowed us to test their ballistic characteristics, limits and efficiency.

After our experimental replicas were shot, we examined the fractures that resulted and compared them with those found on the archeological material. The fractures and scars show that they were distally hafted – attached to the split end of a shaft. Their small size and especially narrow width allow us to conclude how they were fired: only high-speed propulsion by a bow was possible, our analysis determined.

The data from the Mandrin cave and the tests that we performed enrich our knowledge of these technologies in Europe and now allow us to push back the age of archery in Europe by more than 40,000 years.

Our study also sheds light on the weaponry of these Neanderthal populations, who were contemporaries of the Neronian modern humans. Neanderthals did not develop mechanically propelled weapons and continued to use their traditional weapons based on the use of massive stone-tipped spears that were thrust or thrown by hand, and thus requiring close contact with the game they hunted. The traditions and technologies mastered by these two populations were thus distinct, illustrating a remarkable objective technological advantage for modern populations during their expansion into Europe.

Not only do these discoveries profoundly reshape our knowledge of Neanderthals and modern humans in Western Europe, but they also raise many questions about the structure and organization of these different populations on the continent. Technical choices are not solely the result of the cognitive capacities of differing hominin populations, but may also have depended on the weight of traditions within these Neanderthal and modern human populations.

To deepen one’s understanding the complex question of the relationship between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals during the first migration to the European continent, the reader can turn to Ludovic Slimak’s book “Néandertal nu” (Odile Jacob 2022), soon available from Penguin books as “The Naked Neanderthal”.

Laure Metz, Archéologue et chercheuse en anthropologie, Aix-Marseille Université (AMU); Jason E. Lewis, Lecturer of Anthropology and Assistant Director of the Turkana Basin Institute, Stony Brook University (The State University of New York), and Ludovic Slimak, CNRS Permanent Member, Université Toulouse – Jean Jaurès

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.