A Mission for Nutrition

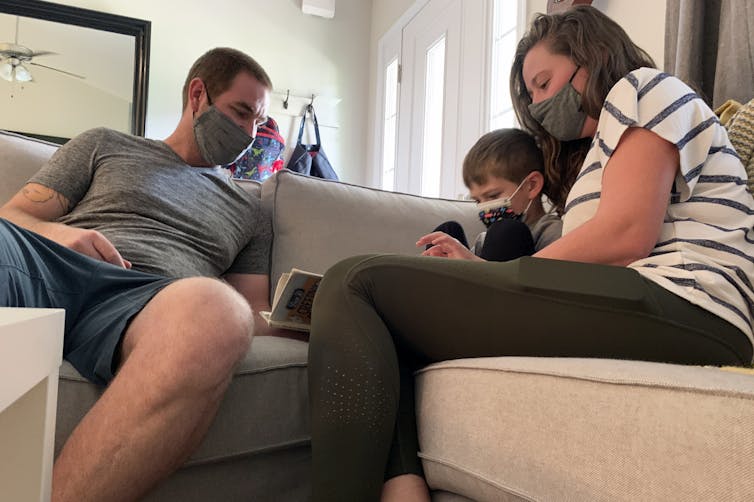

Accomplish health goals with better-for-you family meals

Setting out on a mission to eat healthier starts with creating goals and working to achieve them with those you love. To help make nutritious eating more manageable, call together your family and work with one another to create a menu everyone can enjoy while staying on track.

Connecting an array of recipes that all can agree on starts with versatile ingredients like dairy. Gathering at the table with your loved ones while enjoying delicious, nutritious recipes featuring yogurt, cheese and milk can nourish both body and soul.

For example, the key dairy ingredients in these recipes from Milk Means More provide essential nutrients for a healthy diet. The cheese varieties in Feta Roasted Salmon and Tomatoes and 15-Minute Weeknight Pasta provide vitamin B12 for healthy brain and nerve cell development and are a good source of calcium and protein, which are important for building and maintaining healthy bones. Meanwhile, the homemade yogurt sauce served alongside these Grilled Chicken Gyros provides protein and zinc.

To find more nutritious meal ideas to fuel your family’s health goals, visit MilkMeansMore.org.

Feta Roasted Salmon and Tomatoes

Recipe courtesy of Marcia Stanley, MS, RDN, Culinary Dietitian, on behalf of Milk Means More

Prep time: 15 minutes

Cook time: 15 minutes

Servings: 4

- Nonstick cooking spray

- 3 cups halved cherry tomatoes

- 2 teaspoons olive oil

- 1 teaspoon minced garlic

- 1/2 teaspoon dried oregano or dried dill weed

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon coarsely ground black pepper, divided

- 1 1/2 pounds salmon or halibut fillets, cut into four serving-size pieces

- 1 cup (4 ounces) crumbled feta cheese

- Preheat oven to 425 F. Line 18-by-13-by-1-inch baking pan with foil. Lightly spray foil with nonstick cooking spray. Set aside.

- In medium bowl, toss tomatoes, olive oil, garlic, oregano or dill weed, salt and 1/4 teaspoon pepper.

- Place fish pieces, skin side down, on one side of prepared pan. Sprinkle with remaining pepper. Lightly press feta cheese on top of fish. Pour tomato mixture on other side of prepared pan. Bake, uncovered, 12-15 minutes, or until fish flakes easily with fork.

- Place salmon on serving plates. Spoon tomato mixture over top.

Grilled Chicken Gyros

Recipe courtesy of Kirsten Kubert of "Comfortably Domestic" on behalf of Milk Means More

Prep time: 30 minutes, plus 30 minutes chill time

Cook time: 20 minutes

Servings: 8

Chicken:

- 3 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

- 2 tablespoons chopped fresh dill

- 1 tablespoon chopped fresh oregano

- 2 cloves garlic, peeled and minced

- 3 tablespoons freshly squeezed lemon juice

- 1 teaspoon kosher salt

- 1/2 teaspoon black pepper

- 2 pounds boneless, skinless chicken breasts

Yogurt Sauce:

- 1 1/2 cups plain, whole-milk yogurt

- 1 1/2 tablespoons freshly squeezed lemon juice

- 1/2 cup diced cucumber

- 2 tablespoons chopped fresh dill

- 1 clove garlic, peeled and minced

- 1/4 teaspoon kosher salt

- 1/8 teaspoon black pepper

- 3-4 small loaves whole-wheat pita bread, halved lengthwise

- 1 cup thinly sliced tomatoes

- 1/2 cup thinly sliced red onion

- To make chicken: Place melted butter, dill, oregano, garlic, lemon juice, salt and pepper in gallon-size zip-top freezer bag. Seal bag and shake contents to combine. Add chicken. Seal bag, pressing air out of bag. Shake chicken to coat with marinade. Refrigerate chicken in marinade 30 minutes.

- To make yogurt sauce: Stir yogurt, lemon juice, diced cucumber, dill, garlic, salt and pepper. Cover sauce and refrigerate.

- Heat grill to medium heat.

- Grill chicken over direct heat, about 10 minutes per side, until cooked through. Transfer chicken to cutting board and rest 10 minutes. Thinly slice chicken across grain.

- Serve chicken on pita bread with tomatoes, red onion and yogurt sauce.

15-Minute Weeknight Pasta

Recipe courtesy of Kirsten Kubert of "Comfortably Domestic" on behalf of Milk Means More

Prep time: 5 minutes

Cook time: 10 minutes

Servings: 6

- 6 quarts water

- 16 ounces linguine or penne pasta

- 2 tablespoons unsalted butter

- 1/2 cup thinly sliced onion

- 1 cup thinly sliced carrots

- 1 cup thinly sliced sweet bell pepper

- 1/2 cup grape tomatoes, halved

- 1 teaspoon kosher salt

- 1/4 teaspoon black pepper

- 2 cloves garlic, peeled and minced

- 1 cup reserved pasta water

- 1 teaspoon finely grated lemon zest

- 1/2 cup smoked provolone cheese, shredded

- 1/4 cup chopped fresh parsley (optional)

- Parmesan cheese (optional)

- Bring water to rolling boil and prepare pasta according to package directions for al dente texture, reserving 1 cup pasta water.

- In large skillet over medium heat, melt butter. Stir in onions, carrots and sweet bell peppers. Saute vegetables about 5 minutes, or until they brighten in color and begin to soften. Add tomatoes, salt, pepper and garlic. Cook and stir 1 minute to allow tomatoes to release juices.

- Pour reserved pasta water into skillet, stirring well. Bring sauce to boil. Reduce heat to medium-low and simmer 3 minutes. Taste sauce and adjust seasonings, as desired.

- Transfer drained pasta to skillet along with lemon zest and smoked provolone cheese, tossing well to coat. Serve immediately with fresh parsley and Parmesan cheese, if desired.

United Dairy Industry of Michigan