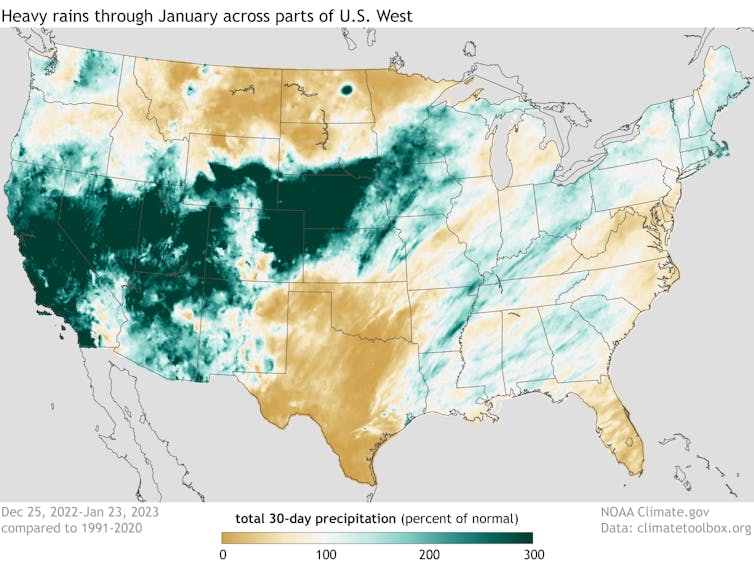

After three years of extreme drought, the Western U.S. is finally getting a break. Mountain ranges are covered in deep snow, and water reservoirs in many areas are filling up following a series of atmospheric rivers that brought record rain and snowfall to large parts of the region.

Many people are looking at the snow and water levels and asking: Is the drought finally over?

There is a lot of nuance to the answer. Where you are in the West and how you define “drought” make a difference. As a drought and water researcher at the Desert Research Institute’s Western Regional Climate Center, here’s what I’m seeing.

How fast each region recovers will vary

The winter of 2023 has made a big dent in improving the drought and potentially eliminating the water shortage problems of the last few summers.

I say “potentially” because in many areas, a lot of the impacts of drought tend to show up in summer, once the winter rain and snow stop and the West starts relying on reservoirs and streams for water. Spring heat waves like the ones we saw in 2021 or rain in the mountains could melt the snowpack faster than normal.

California and the Great Basin

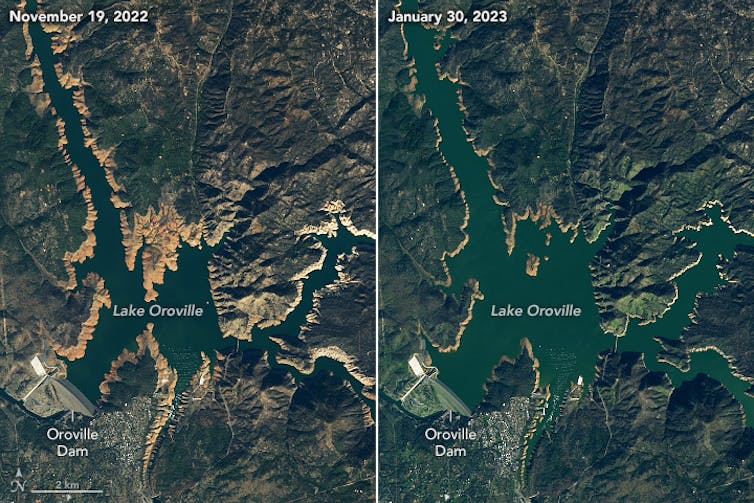

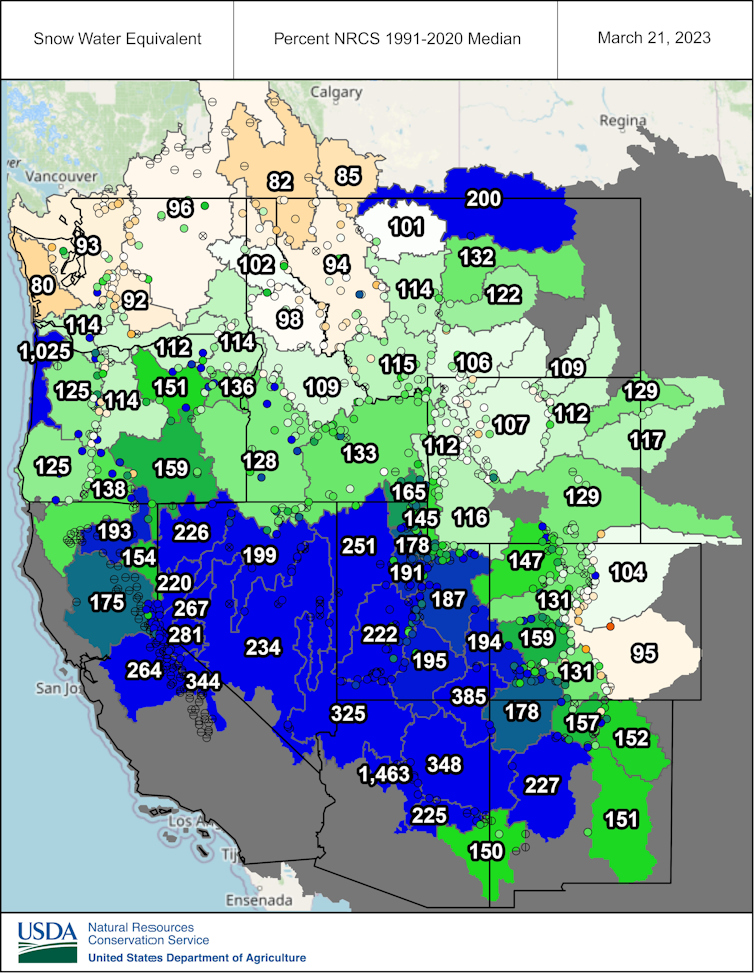

In California, the state’s three-year precipitation deficit was just about erased by the atmospheric rivers that caused so much flooding in December and January. By March, the snowpack across the Sierra Nevada was well above the historical averages – and more than 200% of average in some areas. The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California announced it was ending emergency water restrictions for nearly 7 million people on March 15.

It seems as though most of the surface water drought – drought involving streams and reservoirs – could be eliminated by summer in California and the Great Basin, across Nevada and western Utah.

But that’s only surface water. Drought also affects groundwater, and those effects will take longer to alleviate.

Studies in California have shown that, even after wet years like 2017 and 2019, the groundwater systems did not fully recover from the previous drought, in part because of years of overpumping groundwater for agriculture, and the aquifers were not fully recharging.

In that sense, the drought is not over. But at the broader scale for the region, a lot of the drought impacts that people experience will be lessened or almost gone by this summer.

The Colorado River Basin

Similar to the Sierra Nevada, the Upper Colorado River Basin – Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and northwestern New Mexico – has a healthy snowpack this year, and it’s looking like a very good water year there.

But one single good water year is not going to fill Lake Mead and Lake Powell. Most of the region relies on those two reservoirs, which have declined to worrying levels over the past two decades.

Two good water years won’t do it either. Over the next decade, most years will have to be above average to begin to fill those giant reservoirs. Rising temperatures and drying will make that even harder.

So, that system is still going to be dealing with a lot of the same long-term drought impacts that it has been seeing. The reservoirs will likely rise some, but nowhere close to capacity.

The Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest isn’t having as much rain and snow, and it’s a little drier there. But it’s close to average, so there’s not a huge concern there, at least not right now.

Forests, range land and the fire risk

Drought can also have longer-term impacts on ecosystems, particularly forest health.

The Sierra Nevada range has seen large-scale tree die-offs with the drought in recent years, including in northern areas around Lake Tahoe and Reno that weren’t as affected by the previous drought. Whether the recent die-offs there are due to the severity of the current drought or lingering effects from the past droughts is an open question.

Even with a wet winter, it’s not clear how soon the forests will recover.

Rangelands, since they are mostly grasses, can recover in a few months. The soil moisture is really high in a lot of these areas, so range conditions should be good across the West – at least going into summer.

If the West has another really hot, dry summer, however, the drought could ramp up again, particularly in the Northwest and California. And then communities will have to think about fire risk.

Right now, there’s a below-normal likelihood of big fires in the Southwest for early spring due to lots of soil moisture and snowpack.

In the higher-elevation mountains and forests, the above-average snowpack is likely to last longer than it has in recent years, so those regions will likely have a later start to the fire season. But lower elevations, like the Great Basin’s shrub- and grassland-dominated ecosystem, could see fire danger starting earlier in the year if the land dries out.

Long-term outlooks aren’t necessarily reliable

By a lot of atmospheric measures, California appears to be coming out of drought, and the drought feels like it’s ending elsewhere. But it’s hard to say when exactly the drought is over. Studies suggest the West’s hydroclimate is becoming more variable in its swings from drought to deluge.

Drought is also hard to forecast, particularly long term. Researchers can get a pretty good sense of conditions one month out, but the chaotic nature of the atmosphere and weather make longer-range outlooks less reliable.

We saw that this year. The initial forecast was for a dry winter 2023 in much of the West. But in California, Arizona and New Mexico, the opposite happened.

Seasonal forecasts tend to rely heavily on whether it’s an El Niño or La Niña year, involving sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific that can affect the jet stream and atmospheric conditions around the world. During La Niña – the pattern we saw from 2020 until March 2023 – the Southwest tends to be drier and the Pacific Northwest wetter.

But that pattern doesn’t always set up in exactly the same way and in the same place, as we saw this year.

There is a lot more going on in the atmosphere and the oceans on a short-term scale that can dominate the La Niña pattern. This year’s series of atmospheric rivers has been one example.

Editor’s note: This article was updated on March 22, 2023, with the latest snowpack map.

Dan McEvoy, Associate Research Professor in Climatology, Desert Research Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.