How men’s golf has been shaken by Saudi Arabia’s billion-dollar drive for legitimacy

The first major tournament of 2023 in men’s professional golf could be a particularly tense affair. The Masters, held every April in the US city of Augusta (Georgia), sees the world’s finest players compete for a prize purse of around US$15 million (£12.1m), as well as the famous green jacket for the winner.

Approximately 90 players will compete for that jacket after a tumultuous 12 months for the sport, during which some of the best-known golfers have controversially broken away from the US-based PGA Tour, the biggest and most powerful organiser of professional golf events.

They chose instead to join LIV Golf, a new rival tour funded by Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, causing a significant rift among golf’s leading male professionals. Now in the early stages of its crucial second season, with US$2 billion (£1.65 billion) having been invested, LIV Golf is taking a real swing at the golfing establishment.

Our recent research suggests that LIV Golf was constructed not simply to add an extra layer to the men’s professional game or create a breakaway league. In fact, it appears designed to reshape men’s professional golf entirely.

From the outset, LIV Golf promised to be “golf, but louder” – with shorter rounds, limited competitor fields, and lots and lots of money – to make the sport more attractive to new spectators.

A defensive PGA Tour immediately lashed out, banning any players who joined LIV Golf from its own competitions. LIV Golf responded by saying the PGA Tour was being “vindictive” and divisive.

Top players came out fighting for both sides. And while LIV Golf was initially labelled “dead in the water” by Northern Ireland’s four-time major champion Rory McIlroy in early 2022, not everyone agreed. High-profile defections from the PGA Tour to LIV Golf included major champions Phil Mickelson, Dustin Johnson, Brooks Koepka, Bryson DeChambeau, and the 2022 Open Champion Cameron Smith.

But despite huge cash prizes and big-name players, LIV Golf is not yet the roaring success it was designed to be. Sponsors and broadcasters are not desperate to get involved, and many of the first season’s events were only broadcast on Facebook and YouTube channels.

This rival tour still faces significant challenges. Encouraging more players to defect and gaining more broadcast deals – including improving on the one that involves LIV Golf paying an American network to cover its events – will be the gameplan.

Level playing field?

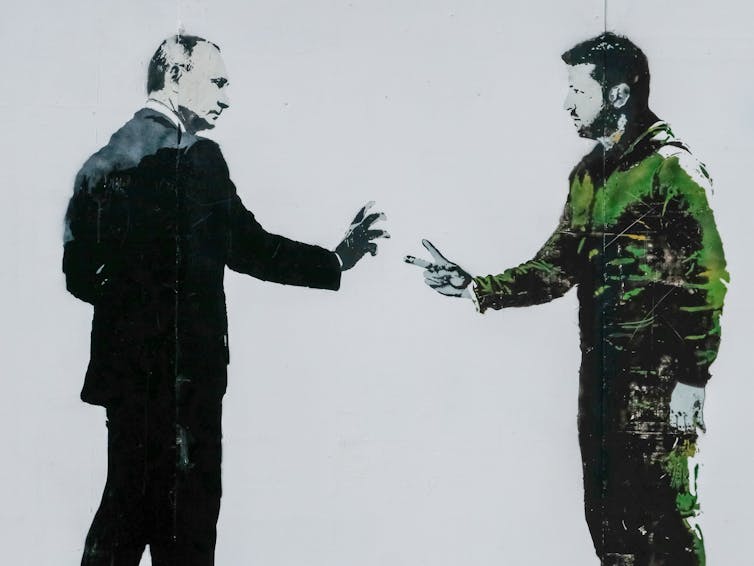

But this is not just about golf. The expensive creation of a rival tour is just part of Saudi Arabia’s ongoing push for legitimacy in the sporting world. And what some call “legitimacy”, others call “sportswashing” – the use of sport by oppressive governments or leaders to distract the rest of the world from from human rights abuses in a bid for soft power.

For Saudi Arabia, LIV Golf is part of a wider economic strategy which seeks to diminish the Gulf state’s reliance on oil. Other sports including Formula 1, football and boxing are already in play.

But where does this leave the future of professional golf? LIV Golf claimed that its goal is to “improve the health of professional golf” and “help unlock the sport’s untapped potential”.

There is perhaps some truth in this. Despite the controversy, McIlroy has since reflected that it was a shakeup the PGA Tour needed in order to innovate and adapt. He now believes LIV has benefited everyone who plays professional golf at a high level.

As LIV Golf celebrated the beginning of a new season in February 2023, amid reports of possible financial penalties for LIV players if they decide they want to return to the PGA Tour, it is clear the organisation is not going away.

For the moment it continues to battle for supremacy of the men’s professional game, both on the course and in court. However – ethical issues and a lack of external commercial backing notwithstanding – it’s possible the PGA Tour and LIV Golf could eventually manage to co-exist.

The introduction of LIV Golf has also led to the men’s four major tournaments (the Masters, PGA Championship, US Open and the UK’s Open Championship) becoming even more crucial for players to win. LIV has also made the majors more important for golf fans, as these are now the only men’s events where they get to watch a full-strength field from all tours.

The 2023 Masters will be the first time the players from the PGA and LIV tours have competed against each other in almost nine months. In a game all about control and tradition, LIV Golf has succeeded in creating a fair amount of noise. In years to come, that noise could prove loud enough to completely transform an entire global sport.

Leon Davis, Senior Lecturer in Events Management, Teesside University and Dan Plumley, Principal Lecturer in Sport Finance, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Praise effort: It’s easy to fall into the habit of praising successes. However, praising effort encourages children to try new things without the fear of failing. It also teaches children personal growth and achievement are possible, even if their overall effort wasn’t a success.

Praise effort: It’s easy to fall into the habit of praising successes. However, praising effort encourages children to try new things without the fear of failing. It also teaches children personal growth and achievement are possible, even if their overall effort wasn’t a success.