Regulating AI: 3 experts explain why it’s difficult to do and important to get right

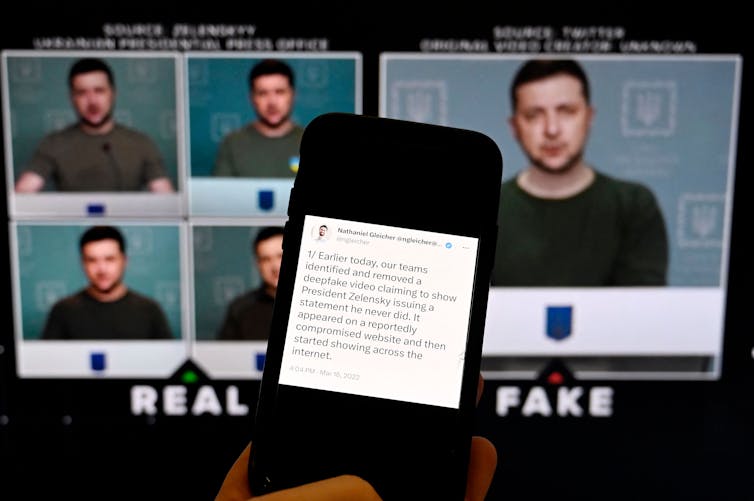

From fake photos of Donald Trump being arrested by New York City police officers to a chatbot describing a very-much-alive computer scientist as having died tragically, the ability of the new generation of generative artificial intelligence systems to create convincing but fictional text and images is setting off alarms about fraud and misinformation on steroids. Indeed, a group of artificial intelligence researchers and industry figures urged the industry on March 29, 2023, to pause further training of the latest AI technologies or, barring that, for governments to “impose a moratorium.”

These technologies – image generators like DALL-E, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion, and text generators like Bard, ChatGPT, Chinchilla and LLaMA – are now available to millions of people and don’t require technical knowledge to use.

Given the potential for widespread harm as technology companies roll out these AI systems and test them on the public, policymakers are faced with the task of determining whether and how to regulate the emerging technology. The Conversation asked three experts on technology policy to explain why regulating AI is such a challenge – and why it’s so important to get it right.

To jump ahead to each response, here’s a list of each:

Human foibles and a moving target

Combining “soft” and “hard” approaches

Four key questions to ask

Human foibles and a moving target

S. Shyam Sundar, Professor of Media Effects & Director, Center for Socially Responsible AI, Penn State

The reason to regulate AI is not because the technology is out of control, but because human imagination is out of proportion. Gushing media coverage has fueled irrational beliefs about AI’s abilities and consciousness. Such beliefs build on “automation bias” or the tendency to let your guard down when machines are performing a task. An example is reduced vigilance among pilots when their aircraft is flying on autopilot.

Numerous studies in my lab have shown that when a machine, rather than a human, is identified as a source of interaction, it triggers a mental shortcut in the minds of users that we call a “machine heuristic.” This shortcut is the belief that machines are accurate, objective, unbiased, infallible and so on. It clouds the user’s judgment and results in the user overly trusting machines. However, simply disabusing people of AI’s infallibility is not sufficient, because humans are known to unconsciously assume competence even when the technology doesn’t warrant it.

Research has also shown that people treat computers as social beings when the machines show even the slightest hint of humanness, such as the use of conversational language. In these cases, people apply social rules of human interaction, such as politeness and reciprocity. So, when computers seem sentient, people tend to trust them, blindly. Regulation is needed to ensure that AI products deserve this trust and don’t exploit it.

AI poses a unique challenge because, unlike in traditional engineering systems, designers cannot be sure how AI systems will behave. When a traditional automobile was shipped out of the factory, engineers knew exactly how it would function. But with self-driving cars, the engineers can never be sure how it will perform in novel situations.

Lately, thousands of people around the world have been marveling at what large generative AI models like GPT-4 and DALL-E 2 produce in response to their prompts. None of the engineers involved in developing these AI models could tell you exactly what the models will produce. To complicate matters, such models change and evolve with more and more interaction.

All this means there is plenty of potential for misfires. Therefore, a lot depends on how AI systems are deployed and what provisions for recourse are in place when human sensibilities or welfare are hurt. AI is more of an infrastructure, like a freeway. You can design it to shape human behaviors in the collective, but you will need mechanisms for tackling abuses, such as speeding, and unpredictable occurrences, like accidents.

AI developers will also need to be inordinately creative in envisioning ways that the system might behave and try to anticipate potential violations of social standards and responsibilities. This means there is a need for regulatory or governance frameworks that rely on periodic audits and policing of AI’s outcomes and products, though I believe that these frameworks should also recognize that the systems’ designers cannot always be held accountable for mishaps.

Combining ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ approaches

Cason Schmit, Assistant Professor of Public Health, Texas A&M University

Regulating AI is tricky. To regulate AI well, you must first define AI and understand anticipated AI risks and benefits. Legally defining AI is important to identify what is subject to the law. But AI technologies are still evolving, so it is hard to pin down a stable legal definition.

Understanding the risks and benefits of AI is also important. Good regulations should maximize public benefits while minimizing risks. However, AI applications are still emerging, so it is difficult to know or predict what future risks or benefits might be. These kinds of unknowns make emerging technologies like AI extremely difficult to regulate with traditional laws and regulations.

Lawmakers are often too slow to adapt to the rapidly changing technological environment. Some new laws are obsolete by the time they are enacted or even introduced. Without new laws, regulators have to use old laws to address new problems. Sometimes this leads to legal barriers for social benefits or legal loopholes for harmful conduct.

“Soft laws” are the alternative to traditional “hard law” approaches of legislation intended to prevent specific violations. In the soft law approach, a private organization sets rules or standards for industry members. These can change more rapidly than traditional lawmaking. This makes soft laws promising for emerging technologies because they can adapt quickly to new applications and risks. However, soft laws can mean soft enforcement.

Megan Doerr, Jennifer Wagner and I propose a third way: Copyleft AI with Trusted Enforcement (CAITE). This approach combines two very different concepts in intellectual property — copyleft licensing and patent trolls.

Copyleft licensing allows for content to be used, reused or modified easily under the terms of a license – for example, open-source software. The CAITE model uses copyleft licenses to require AI users to follow specific ethical guidelines, such as transparent assessments of the impact of bias.

In our model, these licenses also transfer the legal right to enforce license violations to a trusted third party. This creates an enforcement entity that exists solely to enforce ethical AI standards and can be funded in part by fines from unethical conduct. This entity is like a patent troll in that it is private rather than governmental and it supports itself by enforcing the legal intellectual property rights that it collects from others. In this case, rather than enforcement for profit, the entity enforces the ethical guidelines defined in the licenses - a “troll for good.”

This model is flexible and adaptable to meet the needs of a changing AI environment. It also enables substantial enforcement options like a traditional government regulator. In this way, it combines the best elements of hard and soft law approaches to meet the unique challenges of AI.

Four key questions to ask

John Villasenor, Professor of Electrical Engineering, Law, Public Policy, and Management, University of California, Los Angeles

The extraordinary recent advances in large language model-based generative AI are spurring calls to create new AI-specific regulation. Here are four key questions to ask as that dialogue progresses:

1) Is new AI-specific regulation necessary? Many of the potentially problematic outcomes from AI systems are already addressed by existing frameworks. If an AI algorithm used by a bank to evaluate loan applications leads to racially discriminatory loan decisions, that would violate the Fair Housing Act. If the AI software in a driverless car causes an accident, products liability law provides a framework for pursuing remedies.

2) What are the risks of regulating a rapidly changing technology based on a snapshot of time? A classic example of this is the Stored Communications Act, which was enacted in 1986 to address then-novel digital communication technologies like email. In enacting the SCA, Congress provided substantially less privacy protection for emails more than 180 days old.

The logic was that limited storage space meant that people were constantly cleaning out their inboxes by deleting older messages to make room for new ones. As a result, messages stored for more than 180 days were deemed less important from a privacy standpoint. It’s not clear that this logic ever made sense, and it certainly doesn’t make sense in the 2020s, when the majority of our emails and other stored digital communications are older than six months.

A common rejoinder to concerns about regulating technology based on a single snapshot in time is this: If a law or regulation becomes outdated, update it. But this is easier said than done. Most people agree that the SCA became outdated decades ago. But because Congress hasn’t been able to agree on specifically how to revise the 180-day provision, it’s still on the books over a third of a century after its enactment.

3) What are the potential unintended consequences? The Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act of 2017 was a law passed in 2018 that revised Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act with the goal of combating sex trafficking. While there’s little evidence that it has reduced sex trafficking, it has had a hugely problematic impact on a different group of people: sex workers who used to rely on the websites knocked offline by FOSTA-SESTA to exchange information about dangerous clients. This example shows the importance of taking a broad look at the potential effects of proposed regulations.

4) What are the economic and geopolitical implications? If regulators in the United States act to intentionally slow the progress in AI, that will simply push investment and innovation — and the resulting job creation — elsewhere. While emerging AI raises many concerns, it also promises to bring enormous benefits in areas including education, medicine, manufacturing, transportation safety, agriculture, weather forecasting, access to legal services and more.

I believe AI regulations drafted with the above four questions in mind will be more likely to successfully address the potential harms of AI while also ensuring access to its benefits.

S. Shyam Sundar, James P. Jimirro Professor of Media Effects, Co-Director, Media Effects Research Laboratory, & Director, Center for Socially Responsible AI, Penn State; Cason Schmit, Assistant Professor of Public Health, Texas A&M University, and John Villasenor, Professor of Electrical Engineering, Law, Public Policy, and Management, University of California, Los Angeles

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.