Amyloid plaque can build up in body organs other than the brain. The resulting diseases — AL amyloidosis, ATTR amyloidosis and more — cause much suffering.

Isabelle Lousada was in her early 30s when she collapsed at her Philadelphia wedding in 1995. A London architect, she had suffered a decade of mysterious symptoms: tingling fingers, swollen ankles, a belly distended by her enlarged liver. The doctors she first consulted suggested she had chronic fatigue syndrome or that she’d been partying and drinking too hard.

But her new brother-in-law, a cardiologist, felt that something else must be going on. A fresh series of doctor’s visits led, finally, to the proper diagnosis: Malformed proteins had glommed together inside Lousada’s bloodstream and organs. Those giant protein globs are called amyloid, and the diagnosis was amyloidosis.

Amyloid diseases that affect the brain, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, receive the lion’s share of attention from medical professionals and the press. In contrast, amyloid diseases that affect other body parts are less familiar and rarely diagnosed conditions, says Gareth Morgan, a biochemist at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. Physicians may struggle to recognize and distinguish them, especially in early stages.

Treatment options have also been limited — Lousada, now CEO of the nonprofit Amyloidosis Research Consortium in Newton, Massachusetts, was fortunate to survive thanks to a stem cell transplant that is too grueling or unsuitable for many with amyloidosis.

Several new medications have come out in the last five years — and these, Lousada says, “have been real game-changers.” But although these therapies can block the formation of new, damaging amyloid, they can’t dissolve the amyloid that’s already built up. The body has natural processes to do so, but these are often too slow to clear years’ worth of built-up amyloid, especially in older individuals. And so patients still deal with amyloid clogging their organs, and people still die of amyloidosis, even if they survive longer than they once did.

Scientists are working on newer treatments, including ones that may help a patient’s own immune cells swoop in and destroy residual amyloid.

When folding goes awry

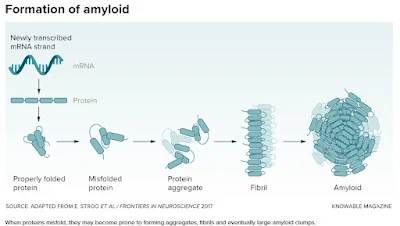

Amyloid structures are natural body proteins gone horribly wrong. When protein formation proceeds normally, the amino acid chains curve and fold just so, like precise origami, to create their final, functional shapes. But sometimes, due to genetic errors or aging, a protein adopts an alternative, inappropriate shape that exposes sticky bits. Misfolded proteins start to clump together into small aggregates, then bigger chains called fibrils, and finally into huge, rectangular structures called amyloid. Amyloid can gum up the workings of cells by just generally getting in the way, but it may also interact with certain other molecules to produce directly toxic effects.

There are a few dozen human proteins that have a propensity to form amyloid, and scientists regularly add more to the list, says Fabrizio Chiti, a biochemist at the University of Florence, Italy, who coauthored a paper on misfolded proteins in disease for the Annual Review of Biochemistry. The body does have ways to identify and dispose of these misfolded proteins, but with age, these defenses tend to falter, so amyloid diseases often strike older people.

One of the more common non-brain amyloid diseases is transthyretin amyloidosis, or ATTR for short; it occurs when a protein called transthyretin misfolds. The normal job of transthyretin is to carry a thyroid hormone and vitamin A in the blood to different parts of the body. When it forms amyloid, the result is different depending on where the malformed proteins land. In the peripheral nerves, the amyloid causes symptoms such as tingling and numbness in extremities. More commonly, amyloid forms in the heart, where it causes symptoms of cardiomyopathy such as abnormal heart rhythm and shortness of breath.

Up to 7,000 new cases of ATTR-cardiomyopathy are diagnosed every year in the United States; more people may have some of this amyloid in the heart without manifesting symptoms, says Morgan. ATTR-cardiomyopathy may account for many more cases of heart disease than physicians currently realize.

Amyloid can form from entirely normal transthyretin. But another, inherited form of the disease occurs when a genetic mutation makes the transthyretin protein particularly likely to misfold. It’s this form that doctors initially suspected after Lousada’s wedding. Hereditary ATTR can occur in people of Portuguese descent, and a physician noticed that Lousada’s last name is Portuguese.

Doctors performed a liver biopsy and used a special stain to identify amyloid, but further studies indicated that ATTR wasn’t the answer. It turned out that Lousada’s kidneys, liver, spleen and heart were chock full of another kind of amyloid, built from a portion of antibody protein.

Our bodies make a huge diversity of antibodies to help defend us against countless foreign threats. But sometimes, one immune cell starts copying itself like crazy, pumping out tons of just one kind of antibody. Perhaps 1 percent of people over the age of 50 have this condition without a problem, says Morgan. But if those immune cells accumulate additional defects they can take over the bone marrow, becoming a type of blood cancer called multiple myeloma. Or if the overproduced antibodies include misfolding segments in a part of the antibody called the light chain, the result is light chain amyloidosis, or AL.

AL amyloidosis causes a variety of symptoms, including, commonly, kidney or heart damage. In later stages, the tongue may swell up with amyloid and blood vessels around the eyes may become damaged. “It’s almost like having black eyes all the time,” says Morgan. Though AL is the other most common form of non-brain amyloidosis, it is only diagnosed up to 3,200 times every year in the United States.

Lousada’s AL diagnosis was made decades back, and she was lucky: Eventually, a therapy worked — but not immediately. Physicians first tried chemotherapy, but her disease continued to worsen, and doctors in London discharged her to hospice care, estimating that she had months to live.

Her brother-in-law came to the rescue again, connecting her with a hospital in Boston that was doing stem cell transplants — a multiple myeloma treatment — for patients with AL. The idea was to wipe out the bone marrow from which immune cells arise, then replace it with new marrow from a donor. This should eliminate the cells that were spewing out the problem light chain protein.

Lousada underwent the treatment, which required months in the hospital, and it took years to fully recover.

Like AL, treatment options for ATTR also were limited and difficult in the past. Most transthyretin is made in the liver, so a liver transplant can help some people with the inherited form. But that leaves patients taking immunosuppressants for life, lest they reject the new liver.

More options were desperately needed, and years back, well before Lousada got sick, researchers were at work on the problem.

A variety of drug approaches

Since 1989, chemical neurobiologist Jeffery Kelly had aimed to develop medication for ATTR. Kelly, now at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California, knew that normal transthyretin consists of four individual proteins joined together, and that, in this form, it cannot misfold or form amyloid. He reasoned that if he could use a small molecule to lock the four transthyretin molecules together in the proper shape, he could stop the protein from taking on a new, damaging one.

Over several studies and more than a decade, Kelly’s team tested about a thousand potential molecules in test tubes for the ability to stabilize transthyretin. When amyloid forms, it makes solutions cloudy or opaque in violet light and near-ultraviolet light, so the scientists could measure when drugs inhibited creation of amyloid. After chemical tweaking of these candidate drugs, they settled on a molecule called tafamidis.

Kelly cofounded a company, FoldRx, to develop the drug; Pfizer took over FoldRx in 2010. In an international trial, researchers studied 128 people who had polyneuropathy due to the transthyretin mutation doctors once suspected in Lousada. The drug slowed the rate at which their symptoms worsened. This study, which focused on people who had neuropathy and was published in 2012, led to approval of tafamidis in several nations. A second trial of 441 patients who had heart disease caused by ATTR showed the drug reduced cardiovascular-related hospitalizations and deaths and slowed decline in quality of life, leading to US Food and Drug Administration approval for ATTR-cardiomyopathy in 2019.

Today, Kelly says, there are about 30,000 people taking tafamidis worldwide. But he thinks many more could benefit if it were easier to diagnose ATTR.

Other researchers are developing drugs using different approaches. For example, while tafamidis stabilizes transthyretin, other scientists have decided to eliminate the protein itself. That’s possible because there are other proteins that can do transthyretin’s transport job, says physician David Lebwohl, chief medical officer for Intellia Therapeutics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The company is using a form of gene therapy to deactivate the transthyretin gene in the livers of ATTR patients.

In an early trial of 15 people with inherited ATTR-polyneuropathy, the treatment was safe and cut the amount of transthyretin present in their blood by an average of 93 percent at the highest dose. Intellia hopes to start a larger trial looking at the drug in ATTR-cardiomyopathy patients by the end of 2023. If successful, Intellia’s treatment would join three other anti-transthyretin gene treatments that have come out in the last five years, inotersen, patisiran and vutrisiran. These medications use small snippets of nucleic acid that block transthyretin from being made, without deactivating the gene itself as Intellia’s strategy does.

Things are also looking up for treatment of AL amyloidosis. In 2021, the FDA approved a treatment containing daratumumab, another medication borrowed from multiple myeloma, specifically for AL. Like the molecule behind the disease, this treatment is an antibody, but an entirely different one. The daratumumab antibody sticks to the problem immune cells that are churning out light chain. It acts as a label that calls in other parts of the immune system to destroy the problem cells. Once they’re gone, they can’t spew out the problematic AL antibody anymore.

And Kelly, inspired by his earlier protein-stabilizing success, hopes to apply the tafamidis strategy to AL. He and Morgan, who used to work in his lab, are on the hunt for small molecules that would lock the antibody light chain in its proper form so it can’t misfold. This is more challenging than for transthyretin, says Morgan, because every person with AL has a different light chain behind their disease. They need a molecule that will stabilize any and all of them.

After screening more than 650,000 small molecules, Morgan and Kelly found several candidates. Based on biochemical tests and studies of the molecular structures, they think these potential drugs slide into the space between any pair of light chains and keep them in their proper shape. The team has done further chemistry to make molecules that do this even better. The next step will be to test these drug candidates on patient blood samples in Morgan’s lab, to see if it can stabilize light chain proteins sampled from people known to have AL. Kelly cofounded another company, Protego, to bring this medication to market. (Kelly also sits on the scientific advisory board of the Amyloidosis Research Consortium.)

Attacking amyloid itself

Although these new drugs stop amyloid from forming, it’s hard to say how much they help with amyloid that’s already present in patients, which can cause ongoing symptoms.

Patients still deal with amyloid clogging their organs, and people still die of amyloidosis, even if they survive longer than they once did.

Scientists suspect that with time, the immune system — at least in younger people — can identify and clear up this residual protein garbage. But some researchers are working on ways to facilitate elimination of amyloid directly, such as by developing antibodies that would lure immune cells to a specific form of amyloid, or even to any form of amyloid. Such pan-amyloid antibodies would, theoretically, benefit not just patients with ATTR or AL, but also those with other amyloid diseases. There already is a new antibody drug for Alzheimer’s, lecanemab, that identifies the amyloid associated with that disease and appears to reduce its amounts.

And Kelly, who co-wrote about diseases of protein maintenance in the Annual Review of Biochemistry, is interested in revving up a natural process called autophagy. This process is used by body cells when they contain something that’s dangerous, damaged or just no longer useful. They shunt the garbage into an acidic bag called the lysosome, where it’s destroyed.

Immune cells, for example, use autophagy to destroy the garbage they take up, which is probably how young people with feisty immune systems can get rid of residual amyloid. But Kelly suspects that some of these autophagy mechanisms go dormant in elderly people, and defects in autophagy have been linked to neurological amyloid diseases.

Augmenting autophagy in older individuals with amyloidosis, Kelly hopes, will allow their aged immune cells to take out the trash properly. Presumably, this would work on any form of amyloid, in the brain or in the body.

To find molecules that would promote autophagy, the team started by testing 940,000 small molecules to identify ones that would promote a destruction of fat droplets, which are natural targets of autophagy, as well as other degradation methods, in cells growing in lab dishes. Then they tested the winners more specifically for autophagy activation, using the disappearance of a green-glowing piece of protein as it was digested to measure successful autophagy. As reported in a preprint, one promising candidate reduced the amount of amyloid in cultured cells that made either one of two well-known amyloids: tau protein amyloid, linked to Alzheimer’s disease, or an amyloid protein associated with what’s known as “mad cow” disease. The researchers still need to figure out the mechanism of the drug, called CCT020312 for now, before starting clinical trials.

The amyloidosis field has come a long way in the last three-plus decades. “It’s a really amazing time to be in this space, because there’s a lot that has happened,” Morgan says. He envisions a day when treatments will combine several approaches: Stop the production of the problem protein, as daratumumab and gene therapy do; stabilize the protein that’s still made, like tafamidis does; and mop up residual amyloid, like the immune system approaches aim to do.

With time, perhaps, more people with amyloidosis will have stunning results like Lousada did, but with far less onerous treatments than a transplant. Twenty-seven years after her diagnosis, she is fully recovered, though she still has regular blood tests to check if the light chain is building up in her body again. She and her husband are raising three children and have moved to the United States, and she’s become an activist for amyloidosis research.

“I really felt, when I came out of this experience, that I could do something that would have more meaning and impact than architecture,” she says. “In every way, it changed the trajectory of my life.”