The famously dry region has long been dismissed as a mostly lifeless wasteland, good for little more than mining of minerals and precious metals. To these researchers, however, it’s a microbial gold mine worthy of protection.

Benito Gómez-Silva is surrounded by nothing. For as far as the eye can see, no plants dot the landscape; no animals amble across the salt-crusted soil that stretches out to the base of distant mountains. Besides some weak wisps of clouds inching slowly past a blazing sun, nothing moves here. The scenery consists exclusively of dirt and rocks.

It’s easy to imagine why Charles Darwin, peering across a nearby expanse of emptiness 187 years ago, proclaimed this region — the Atacama Desert in northern Chile — a place “where nothing can exist.” Indeed, though scattered sources of water support some plant and animal life, for more than a century most scientists accepted Darwin’s conclusion that here in the Atacama’s driest section, called the hyper-arid core, even the most resilient life forms couldn’t last long.

But Darwin was wrong and that’s why Gómez-Silva is here.

Rising before dawn to beat the day’s most brutal heat, we’ve driven for an hour along an increasingly deserted road, watching the terrain grow steadily emptier of plants and human-built structures. After heading south along Chile’s Coast Mountain range, we turn inland towards the Atacama’s heart. Here the University of Antofagasta desert microbiologist will search for a microscopic fungus that he hopes to isolate and grow in his lab.

We’re at the driest non-polar place on Earth, but Gómez-Silva knows there’s water here, hiding in the salt rocks around us. Just like the salt in a kitchen shaker will soak up water in humid weather, the salt rocks absorb tiny amounts of moisture blown in as night-time ocean fog. Then, sometimes for just a few hours, microscopic drops of water coalesce in the nanopores of the salt creating “tiny swimming pools,” Gómez-Silva says — lifelines for microbes that find refuge in the rocks. When moisture and sunlight coincide, these microbial fungi start to photosynthesize and grow their communities, seen as thin, dark lines across the faces of their salt-rock homes. With the gentle tap of the back of a hammer, Gómez-Silva dislodges a few small rocks with particularly prominent markings. They will head to his lab, where his team will break them down and try to extract the microbes inside and keep them alive in laboratory dishes.

Gómez-Silva is part of a small but strong contingency of scientists searching for living microbes here in the world’s oldest desert, a place that’s been dry since the late Jurassic dinosaurs roamed Earth some 150 million years ago. Anything trying to survive here has a host of challenges to contend with beyond the lack of water: intense solar radiation, high concentrations of noxious chemicals and key nutrients in scarce supply. Yet even so, unusual and tiny things do grow, and researchers like Gómez-Silva say that scientists have a lot to learn from them.

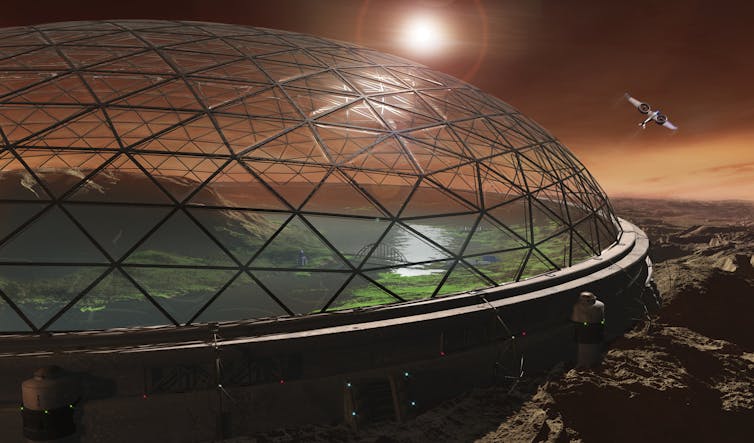

Part of unlocking those secrets involves changing the world’s view of the Atacama, he says, a region that historically has been valued for mining precious minerals above all else. Coauthor of a 2016 Annual Review of Microbiology paper on the desert’s microbial resources, Gómez-Silva is one of several researchers who believe that the Atacama should be prized for something altogether different: as a place to characterize unknown life forms. Describing such extremophiles — so named because of their ability to thrive in extreme, almost otherworldly conditions — has the potential to develop new tools in biotechnology, to answer questions about the very origins of life and to guide us on how to look for life on other planets.

“For centuries the Atacama was ‘lifeless,’” Gómez-Silva says. “We need to change this concept of the Atacama … because it’s full of microbial life. You just need to know where to look.”

Extreme conditions

The Atacama stretches some 600 miles along the coast of South America — its borders aren’t precise — and is flanked on the east by the volcanic Altiplano of the Andes Mountain range and to the west by Chile’s Pacific shores. Roughly the size of Cuba, the desert is as varied as it is hostile.

Yet, despite the desolation, scattered treasures attract visitors from around the world. Near the town of San Pedro, about 150 miles to the east of Gómez-Silva’s university, tourists make trips to see the Atacama’s strange moonlike valleys, the lagunas that serve as oases for migrating flamingos and Chile’s El Tatio geyser field. The desert includes a series of plateaus, ranging in elevation from around sea level to more than 11,000 feet, making it one of the highest deserts in the world. Various international observatories take advantage of that altitude and the desert’s record-low moisture to snap clear pictures of the stars.

The Atacama’s harsh conditions are thanks to the features that mark its borders. Storm fronts moving in from the east rarely breach the towering peaks of the Andes mountains and a thick current of cold ocean waters moving up from Antarctica chills the air along Chile’s coastline, hampering its ability to carry moisture inland. Many parts of this desert receive mere millimeters of rain each year, if any at all. The Atacama Desert city of Arica, just below Peru’s border, holds the record for the world’s longest dry spell — researchers believe not a single drop of rain fell within its borders for more than 14 years in the early 1900s.

Without water, little should survive: Cells shrivel, proteins disintegrate and cellular components can’t move about. The atmosphere at the desert’s high altitudes does little to block the sun’s damaging rays. And the lack of flowing water leaves precious metals in place for mining companies, but means distribution of nutrients through the ecosystem is limited, as is the dilution of toxic compounds. Where water bodies do exist in the desert — often in the form of seasonal basins fed by subterranean rivers — they frequently have high concentrations of salts, metals and elements, including arsenic, that are toxic to many cells. Desert plants and animals that manage to make it in the region typically cling to the desert’s outskirts or to scattered fog oases, which are periodically quenched by dense marine fogs called camanchacas.

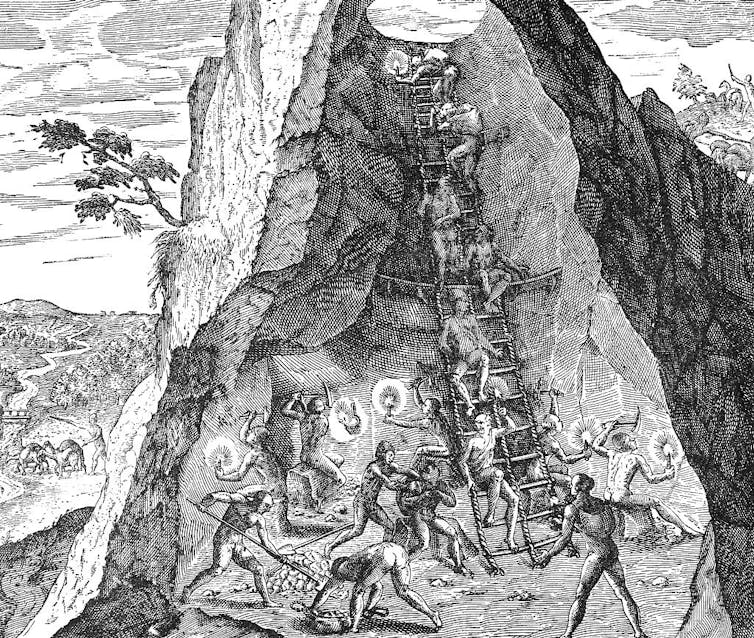

Seeing such conditions on an 1850s expedition to the Atacama at the behest of the Chilean government, even German-Chilean naturalist Rodulfo Philippi, who first documented many of the plants and animals that live in the less extreme parts of the Atacama, emphasized that the desert’s value lay in mineral mining, even as he lamented the challenges of unearthing it due to the region’s desolation.

Mineral mining was more than enough to make the Atacama desirable for Chile, which annexed the area in a bloody, nearly five-year war against Peru and Bolivia that ended in 1883. At the time, the three nations were vying to control reserves of saltpeter — a source of nitrates used in fertilizer and explosives and nicknamed “white gold” — due to massive global demand.

Saltpeter from the ground lost its appeal in the first half of the 20th century when scientists discovered a method for manufacturing nitrates industrially, eliminating the need to dig for them. That spelled death for the saltpeter mines and the towns built up around them. But mining still thrives in the Atacama: Today, Chile is the world’s No. 1 exporter of copper, among the top for lithium, and a major supplier of silver and iron, among other valuable metals and minerals.

Mining has made its mark all through the Atacama Desert. Viewed from space, the Salar de Atacama, a salt flat nearly four times the size of New York City, displays the pale-hued swatches of lithium mines. Gold and copper mines appear as cowlicks, scarring the desert’s surface. On the ground, too, relics of the region’s mining history are not hard to find. Near where Gómez-Silva collects fungi-streaked salt rocks in the Yungay region lies a cemetery with graves dating from the 1800s into the mid-20th century. They are the workers of the abandoned saltpeter mines and their families.

“Life here wasn’t easy,” Gómez-Silva says as he looks down at the headstones of young children lost during that time.

Hidden scientific wealth

A short drive down a dirt road carved through more dirt and small boulders, remnants of science past are also baking under the already punishing morning sun. In 1994, the University of Antofagasta set up a small research station in Yungay with support from NASA, whose astronomers were interested in the Atacama’s harsh, Mars-like conditions. The station was funded only for a few short years, but even after its abandonment the simple structures and the surrounding feeble trees, planted by the university, continued to serve as an unserviced outpost for researchers from all over the world who wanted to know if and how life could endure in such desolate conditions.

On the walls of rooms that once served as the station’s laboratory and kitchen, Gómez-Silva points out where visiting researchers across almost two decades marked their names on the now-peeling paint. Gómez-Silva has spent most of his career in Antofagasta and he fondly remembers a number of the visitors, some of whom have gone on to publish key studies on the limits of life in the desert.

“When we came down to stay at the station starting in 2001, we brought everything with us: showers, toilets, generators, pumps, kitchen sink…” recalls Chris McKay, an astrogeophysicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, whose name is still visible, written in ink on the Yungay research station wall. But despite the humble settings and the lack of water, “it was magical,” he says. “We would sit around after dinner and talk science. There was no phone, no internet, just us.”

It was NASA investigators who kicked off research into whether life might survive in the dry soils and rocks here in the mid-1960s. But it wasn’t until 2003, when a high-profile paper detailed why the desert was a good analog for Mars, that microbial research in the area really started to take off. Investigations of the Atacama have increased steadily since with scientists from fields including ecology, genetics and microbiology joining the effort.

Still, scientists have just scratched the surface; the majority of life here is still unknown, says Cristina Dorador, an Atacama microbiologist at the University of Antofagasta. Dorador is one of 155 elected representatives who worked to draft a new constitution for Chile — now awaiting a public vote — after a 2020 vote to replace the nation’s current dictatorship-era document. Part of Dorador’s goal in joining Chile’s constitutional convention, she says, was to help promote the importance of preserving and studying rare environments, like those of the Atacama, that have traditionally been valued only for the resources that could be extracted from them.

“When the country makes an economic decision, they don’t think about what’s happening with bacteria,” Dorador says. “I’m trying to communicate why it’s important to know about and protect those ecosystems.”

Dorador studies microbial mats that thrive beneath the crust of the Atacama salars, or salt flats, that are sometimes submerged under a layer of brine. A slice through one of these mats yields what might be taken for an alien serving of gelatinous lasagna. Inside the pasta-dish-gone-wrong, which can grow to several centimeters thick and is held together in part by cell-exuded goo, live millions of microorganisms of various types. The species cluster together into distinct, colorful layers: Purple streaks often represent bacteria that can avoid oxygen; bright green stripes might indicate ones that produce it. Other colors hint at cells that can capture nitrogen from their surroundings, produce foul-smelling sulfur, or leak methane or carbon dioxide into the air.

The layering results in a community whereby cells of different species can symbiotically exploit one another’s chemical byproducts. Sometimes, the layers rearrange, taking advantage of changing conditions, like a plant might tilt its leaves to best capture the rays of the sun. “They’re just one of my favorite things in the world,” Dorador says.

They are also a glimpse into the past, as this layered community looks very much like what scientists believe were the earliest ecosystems to come about on Earth. As they grow, some microbial mats form mounds of layered sediment that can be left behind as lithified fossils, called stromatolites. The oldest of these stromatolites date back to 3.7 billion years, when Earth’s atmosphere was devoid of oxygen. Thus, living mats, still found in extreme environments the world over, are of great interest to researchers trying to piece together the puzzle of how life as we know it today came to be.

One of those researchers is University of Connecticut astrobiologist Pieter Visscher. Along with colleagues, he has amassed evidence from stromatolite fossils and modern microbial mats suggesting that early-Earth microbes might have used arsenic for photosynthesis in place of the atmospheric oxygen that wasn’t yet around. Throughout his career, Visscher was plagued by a major conundrum in trying to connect today’s mats to their stromatolitic ancestors. The presence of oxygen in the waters around them, he says, would always mean that the naturally occurring mats he studied couldn’t really show him how those early lifeforms functioned.

Then, on a 2012 trip with Argentinian and Chilean colleagues, Visscher found what he was looking for in a vibrant purple microbial mat thriving below the surface of the Atacama’s La Brava, a hypersaline lake more than 7,500 feet above sea level. Unlike previously studied microbial mats, Visscher couldn’t detect oxygen in the La Brava mats or the waters around them then nor during several subsequent visits at different times of the year. Thus they provide an ideal natural laboratory, he says, and have lent weight to earlier theories about the importance of arsenic for early life.

“I had been looking for well over 30 years to find the right analog,” he says. “This bright purple microbial mat may have been something that was on Earth very early on — 2.8 to 3 billion years ago.”

No zoo for microbes

Creative survival strategies abound in the Atacama, attracting scientists keen to understand how life may have shifted over time. In 2010, a Chilean team reported the discovery of a new species of microbes living off the dew collecting on spiderweb threads in a coastal Atacama cave well-positioned to swallow early morning fog. The Dunaliella, a form of green unicellular alga, was the first of its genus to be found living outside aquatic environments, and its discoverers suggested that its adaptation might be like ones that primitive plants made when first colonizing land.

Other microbes take an active role in seeking out water. In 2020, a group of scientists from the United States described in PNAS a bacterium living within gypsum rocks that secreted a substance to dissolve the minerals around it, releasing individual water molecules sequestered inside the rock.

“They’re almost like miners … digging for water,” says David Kisailus, a chemical and environmental engineer at the University of California, Irvine, and one of the study’s authors. “They can actually search out and find the water and extract the water from these rocks.”

Examples like these are just a taste of what Atacama’s microbes might teach us about survival at extremes, Kisailus says. And such lessons might prime us to recognize clues in the search for life on other worlds, or help us adapt to the environmental changes coming to our own. They’ve turned Dorador, who has seen unique salar ecosystems altered dramatically through water lost to mining and other industries, into an advocate for microbial conservation in the desert.

But it’s a challenge, she says, to argue for the protection and the value of life that can’t be seen. Perhaps if people could witness for themselves a cell foraging for nutrients in boiling water or springing to life from a desiccated state when moisture fills the air, they would be impressed and care about preserving those species. But preservation itself is complicated. The Atacama extremophiles are so specialized that most wouldn’t last long outside their alien environments — scientists can’t even keep many of them alive in the lab.

“We don’t have a zoo of microbes,” Dorador says. “To conserve microbes, we have to conserve their habitats.”

Thinking macroscopically

Arguments for microbial conservation and exploration go beyond scientific curiosity, says Michael Goodfellow, an emeritus professor of microbial systematics at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom. Goodfellow spent much of his career searching for new species of microbes in extreme environments like the Atacama, Antarctica and deep ocean trenches in the hopes of identifying new molecules for use in antibiotics. He thinks such bioprospecting in extreme environments should be considered a critical strategy in confronting the world’s impending antibiotic resistance crisis, which kills at least 700,000 people a year globally.

On their early trips to the Atacama’s hyper-arid core, Goodfellow and his colleagues weren’t really expecting to find much, but still thought it prudent to visit the “neglected habitat” where “hardly any work had been done at all.” To their surprise, they were able to isolate a small number of soil bacteria from the group Actinomycetes, a globally common kind of soil microbe that has long been an important focus of antibiotics research. Since then, work on these microbes has turned up more than 40 new molecules, some of which inhibited common disease-causing bacteria in lab studies.

“Our hypothesis was that the harsh environmental factors were selecting for new organisms that produce new compounds,” says Goodfellow, a coauthor of the Annual Review of Microbiology paper. “Ten years later, I think we’ve proven that hypothesis.”

Bioprospecting in deserts like the Atacama has technological applications as well, says Michael Seeger, a biochemist at the Federico Santa Maria Technical University in Chile. A key example are the microbes responsible for around 10 percent of Chile’s copper production. Copper is often found in a mix of metals, and microbes can help extract it by eating away at other materials in the ore. By giving these microbes free rein of mounds of materials left by mining processes or mixtures of ores where only trace concentrations of copper exist, copper producers can ensure little copper is left behind at their mining sites.

Such metal-munching microbes must be able to handle high levels of acidity because they produce acid as a waste product, which would be deadly for many microbes, says Seeger. To thrive in highly acidic conditions, these acidophiles must have specialized adaptations like cell membranes specialized to block acidic particles, pumps that quickly shunt those damaging elements out of the cell and enzymes capable of making quick repairs to proteins and DNA.

The Atacama is likely to be full of extremophiles like these, with specialized capabilities that make them useful for industry and other practical purposes, says Seeger, who studies the potential of extremophiles to help clean up oil spills and produce bioplastics, among other things. Arsenic-loving microbes might be useful for purifying polluted water sources, and genes borrowed from salt- or drought-tolerant microbes, for example, could be transferred to soil bacteria to boost agriculture in a nation that is facing increasing desertification, he says.

Proteins that function well under extreme conditions could also have important medical applications. Covid PCR tests, for example, would not be possible without a bacterial enzyme that can build DNA strands in extreme temperatures and which was originally plucked from a Yellowstone hot spring. Biologists hope the study of similarly resilient enzymes from desert microbes could lead to additional biotechnological breakthroughs in the future. The Atacama, so extreme in so many different ways, is likely to harbor microbes that are capable of more than we know, Seeger argues, and so it’s crucial to find out what is there.

“When you know what you have, then you can think about what you can do with it,” he says.

Gómez-Silva, for his part, plans to keep working on figuring just what Chile has in the Atacama. For two years he was unable to visit his desert sampling sites because of strict pandemic lockdown restrictions. Now that they are lifted, he’s grateful to be back.

Heading back to the research truck at the end of his sampling trip to Yungay, Gómez-Silva stops and stoops to pick up one last salt rock with a large, dark streak painted across its top.

“How can we not take this one? It’s beautiful,” he says. Then a chuckle. “I don’t know if you can see beauty here. I can.”