Foods of abuse? Nutritionists consider food addiction

Cookies, chips, hot dogs and other ultraprocessed fare raise risk of runaway eating

From the earliest days of their evolution, guts and brains have been the best of friends.

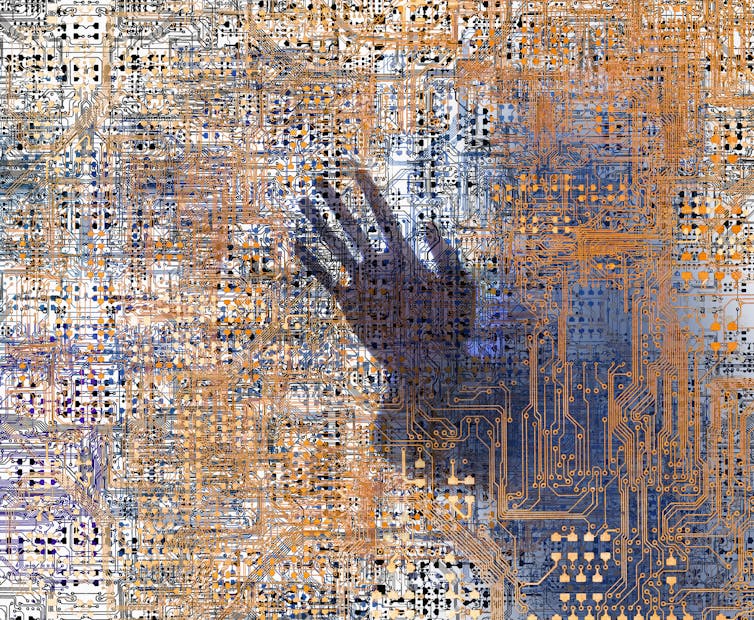

It’s a mutually beneficial relationship. Guts prepare nourishment for delivery to the brain. And brains guide the behaviors needed to fill the gut with raw materials.

Even today, the primitive need to serve the gut’s hunger remains implanted in the human brain’s blueprint for directing behavior. But nowadays, food sometimes drives the brain to behave in ways that aren’t as useful for survival as the original evolutionary programming. In recent decades a mismatch has evolved between the food available to hungry humans and the brain circuitry designed to acquire it. Instead of scrounging for scarce sources of high-quality calories as in the era of hunting and gathering, modern humans are flooded with a glut of ultraprocessed foods, designed to appeal to the brain’s ancient evolutionary imperatives — whether the body needs the food or not.

“Ultraprocessed foods are the result of processing naturally occurring substances … and refining them into evolutionarily novel substances,” Ashley Gearhardt and Erica Schulte write in a review to appear in the 2021 Annual Review of Nutrition. Such substances tempt human taste buds with unnaturally high levels of ingredients that stimulate brain regions related to reward and motivation. As a result, consuming food today can engage behaviors similar to those accompanying addiction to drugs of abuse, write psychologists Gearhardt, of the University of Michigan, and Schulte, who recently moved from the University of Pennsylvania to Drexel University.

Traditionally, addiction experts have dismissed the notion that potato chips or ice cream could be addictive in the same sense as, say, heroin or alcohol. Those drugs can produce debilitating intoxication, and ceasing their use often leads to severe withdrawal symptoms. But by the 21st century, it became clear that tobacco also induces many features of addiction without intoxication. And quitting smoking might make people irritable but it does not inflict intolerable suffering.

“There is now scientific consensus that tobacco is a highly addictive substance,” say Gearhardt and Schulte. “Like tobacco, ultraprocessed foods do not trigger intoxication and do not cause life-threatening physical withdrawal symptoms, but people are prone to compulsively consume them even in the face of significant negative consequences.”

Tobacco’s addictive power demonstrates that addiction is not a simple condition with a clear biological signature that can be measured. Rather, addiction encompasses a cluster of symptoms; not all addicts exhibit all the symptoms. Ultraprocessed foods, Gearhardt and Schulte report, can in some people promote many of the behavioral symptoms associated with addiction to nicotine and other drugs.

Of course, people are always driven to obtain food — like water, it is necessary to survive. Nobody would claim that water is therefore addictive. But brain circuits that evolved to seek high-calorie foods such as nuts, fruits and meat are also stimulated by artificial concoctions loaded with sugars and fats.

Those ultraprocessed foods — such as chips, cookies, pizza and pastries — exploit the desire for tasty, high-calorie meals. So just as addictive drugs hijack the brain’s motivation and reward-seeking circuitry, so do ultraprocessed foods. Many people therefore consume those foods compulsively, despite undesirable consequences including excessive weight gain and various related illnesses, from diabetes to heart disease.

“Ultraprocessed foods have been a key factor in the rising global rates of obesity, diet-related disease and poor health,” Gearhardt and Schulte declare.

Beyond the appeal of sugars and fat, ultraprocessed foods often incorporate additional ingredients, such as attractive coloring, flavor enhancers and stabilizers to make chewing easier — helping deliver the reward to the brain faster and more efficiently.

“Ultraprocessed foods are designed to optimize not only the magnitude of the reward signal in the brain through high doses of calorie-dense ingredients and additives but also the speed with which that reward is delivered,” Gearhardt and Schulte point out.

And while even natural foods may be high in sugar, or in fat, ultraprocessed foods typically offer both extra fat plus sugar in the same package — ready to eat. Add in a vast marketing apparatus (unknown in prehistoric times), and the allure of ultraprocessed foods far exceeds the brain’s intrinsic desire for nutrition.

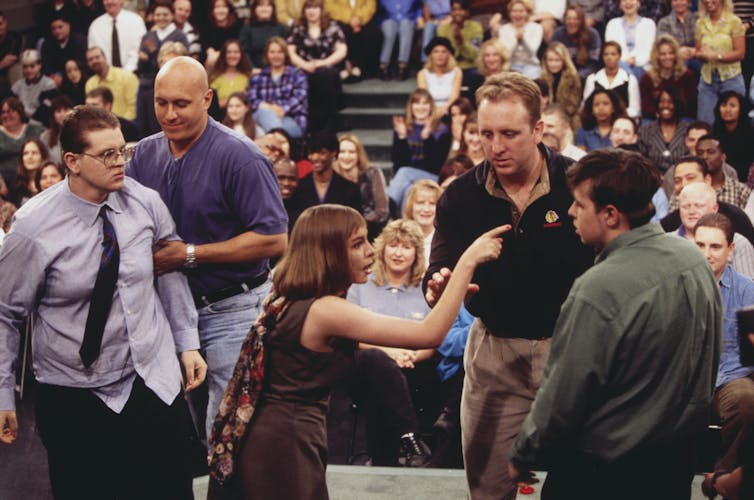

Foods that reward the brain

Remixing natural ingredients into novel concoctions with enhanced appeal was not invented by the food industry. It parallels the methods for preparing traditional addictive drugs by processing natural substances. Natural fruits can be fermented to make addictive drinks, for instance. Tobacco leaves are processed by drying to make nicotine delivery practical. Additional ingredients like sugars in alcoholic drinks and menthol in cigarettes boost the reward signal delivered to the brain. And just as making ultraprocessed foods mimics the manufacture of drugs of abuse, their excessive consumption evokes similar self-destructive behaviors, recent studies have shown.

Those studies have relied on a research tool developed at Yale University called the Yale Food Addiction Scale, based on the behavioral criteria used for diagnosing substance abuse disorders. Such behavioral indicators include lack of control over consuming a substance, continued consumption despite adverse consequences and unsuccessful attempts to cease use of the substance. No one symptom defines addiction; out of 11 symptoms, the presence of two to three indicates mild addiction, four to five suggest moderate addiction, and six or more indicate severe addiction.

Ultraprocessed foods are designed to optimize not only the magnitude of the reward signal in the brain but also the speed with which that reward is delivered.

Studies using the Yale scale show that obesity alone is not diagnostic of food addiction — not all obese people show addictive eating behaviors. But “there is consistent evidence that food addiction is higher for individuals with obesity,” Gearhardt and Schulte note. Such studies suggest that overall, about 15 percent of the US population may have food addiction (roughly the same prevalence as addiction to alcohol). And those studies consistently show that consuming ultraprocessed foods is linked to addictive eating behavior more commonly than natural fruits, vegetables or lean meats.

Besides their addiction-related behaviors, people diagnosed with food addiction on the Yale scale exhibit other similarities to people addicted to drugs. “More intense cravings, higher levels of depression and a greater likelihood of experiencing trauma” are all more common in both groups. Brain scan studies also find similar neural activity patterns in drug addicts and those diagnosed with food addiction.

“Studies using self-report, behavioral and neuroimaging methods have consistently concluded that ultraprocessed foods are the most likely to be associated with features of addiction,” Gearhardt and Schulte report.

Defining the problem

There’s no doubt that ultraprocessed foods motivate more consumption than nutritional needs alone dictate. But some researchers contend that food craving isn’t really a substance abuse disorder like alcoholism, but rather a behavioral addiction, like uncontrolled gambling. Resolving that issue would require identifying which specific chemical substances within the ultraprocessed foods are the key addictive agents.

So far research has not definitively identified such agents. But ultraprocessed foods do appear to evoke chemical changes in the brain (such as cellular sensitivity to some signaling molecules) to an extent that natural foods do not. On the whole, Gearhardt and Schulte conclude, research to date provides more support for the view that food addiction is substance-based rather than just a hard-to-break behavior.

They note, though, that “food addiction” is a term in need of refinement. For one thing, more research is needed to clarify which types of food are addictive and how to define them. Gearhardt and Schulte use “ultraprocessed food” to refer to industrially produced products containing such ingredients as high-fructose corn syrup and other additives. Mostly these foods — such as soft drinks, salty snacks, hot dogs and many other fast foods — overlap with “highly processed” foods spiked with refined carbohydrates and fats. Some are also sometimes called “hyperpalatable foods.”

It’s unclear which labels best identify foods likely to cause addictive behavior. And whether homemade versions of foods such as cookies count as addictive can depend on whether the ingredients used to bake them are processed, such as white flour.

Other issues with terminology enter the debate, of course, with respect to defining “addiction.” Some researchers continue to insist that excessive eating is a behavioral disorder rather than a substance addiction and scoff at the notion that Oreo cookies have anything in common with oxycodone.

But in a larger sense, arguing about whether food is addictive is fruitless. Addiction is not a naturally defined, invariant feature of biology like gravity or electric charge in physics. Addiction is a word. Its use should not be so rigidly constrained that the term can’t be used in ways to better aid those who suffer from self-destructive behaviors.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews.