Social Security is in trouble.

The retirement and disability program has been running a cash-flow deficit since 2010. Its trust fund, which holds US$2.7 trillion, is rapidly diminishing. Social Security’s trustees, a group that includes the secretaries of the departments of Treasury, Labor, and Health and Human Services, as well as the Social Security commissioner, project that the trust fund will be completely drained by 2033.

Under current law, when that trust fund is empty, Social Security can pay benefits only from dedicated tax revenues, which would by that point cover about 77% of promised benefits. Another way to say this is that when the trust fund is depleted, under current law, Social Security beneficiaries would see a sudden 23% cut in their monthly checks in 2034.

As economists who study the Medicare and Social Security programs, we view the above scenario as politically unacceptable. Such a sudden and dramatic benefit cut would anger a lot of voters. Unfortunately, the actions necessary now to avoid it – like raising taxes or cutting benefits – aren’t getting serious consideration today. But we believe there are strategies that could work.

Where the money for benefits comes from

Roughly 67 million Americans, most of whom are 65 or older, receive Social Security benefits. The agency disburses more than $1 trillion annually. It’s the government’s largest single expenditure, constituting nearly 20% of the total federal budget.

Social Security is funded by a payroll tax of 12.4% on wages split equally between workers and employers. Self-employed people pay the entire 12.4%. This payroll tax applies to earnings up to $160,200 as of 2023. The government increases this cap annually based on increases in the National Average Wage Index – a measure that combines wage growth and inflation. The program also receives about 4% of its revenue from a tax on Social Security benefits, though not everyone who receives them has to pay this tax.

Social Security tax revenue stayed relatively flat after 1990. But the costs of the program rose sharply in 2010, in part because of early retirements in response to the Great Recession.

Social Security spending has recently been growing more rapidly because of a wave of baby boomer retirements, which added to a decline in the number of workers per retiree.

Costs of the program are expected to further exceed the money that’s coming in, which will continue to drain the trust fund, according to the program’s trustees.

Barring immediate action by the government, the trust fund’s exhaustion is only a little more than a decade away. And yet few members of Congress seem willing to do something about it. For example, Social Security reform was not even on the table during the 2023 negotiations over the debt ceiling and spending cuts.

Trust fund

Where did the trust fund, which helps cover the program’s costs, come from?

While the Social Security program was collecting surpluses from 1984 to 2009, that extra money funded other spending – keeping other taxes lower than they would have been otherwise and partially covering the budget deficit.

During Social Security’s years of surplus, the excess revenues were credited to the trust fund in the form of special-issue government bonds that yielded the prevailing interest rates. When those bonds are needed to pay for Social Security expenses, the Treasury redeems them.

Those bonds are components of the government’s $31.4 trillion gross debt.

Last reformed during the Reagan administration

Reducing the benefits current retirees receive would be extremely unpopular. Likewise, people now in the workforce who are nearing retirement would certainly object strongly if they were told to expect lower benefits in retirement than they have been promised throughout their careers.

The last time the government made big changes to Social Security was in 1983, during the Reagan administration, when the government enacted reforms that slowly reduced benefits over time. These changes included raising the full retirement age, a change that is still being phased in. Because of those changes, workers born in 1960 or later cannot retire with full benefits until age 67 – two years later than the original retirement age.

The 1983 reforms also included increases in the Social Security payroll tax rate from 10.4% in 1983 to 12.4% by 1990, and for the first time levied federal income taxes on higher-income retirees’ benefits. Workers bore the burden of the payroll tax increases and higher-income retirees bore the burden of the tax on benefits.

Those changes bolstered the program’s finances, but they no longer suffice.

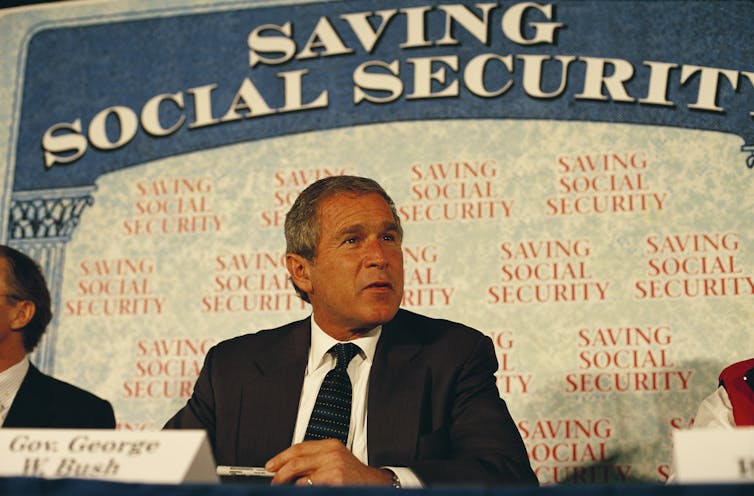

The bipartisan 2001 Commission to Strengthen Social Security tried – and failed – during George W. Bush’s presidency to get Congress to enact reforms to shore up the program’s finances. There’s been no momentum toward resolving the problem since then.

4 principles

We believe that policymakers and lawmakers need to follow four principles as they consider how to move forward.

The program should be self-funded in the long run so that its annual revenues match its annual expenses. That way the many questions that arise related to trust fund accounting and whether Social Security tax revenues are being used for their intended purposes would be eliminated.

The reform burden should be shared across generations. Current retirees can share the burden through a reform that reduces the cost-of-living adjustment. Today’s workers can share the burden through an increase in the cap on income subjected to Social Security taxes so that 90% of total earnings are taxed. Continued gradual increases in the retirement age to keep pace with anticipated longevity gains would also be borne by current workers.

The government should make sure that Social Security benefits will be adequate for lower-income retirees for years to come. That means reforms that slow the benefit growth of future retirees would be designed to affect only higher-income retirees.

Any changes to Social Security should help constrain the future growth of federal spending, given the current and projected growth in the budget deficit.

Advantages of ending the delay

It appears that the U.S. – citizens and elected officials included – are deferring serious debate on this urgent matter until the trust fund’s depletion is imminent. That’s unwise. Acting sooner rather than later would leave more options available to gradually resolve the program’s financial shortfalls.

Ending this procrastination would also give the millions of people who rely on Social Security benefits, taxpayers and businesses more time to prepare for any changes required by overdue reforms.

Andrew Rettenmaier, Executive Associate Director of the Private Enterprise Research Center, Texas A&M University and Dennis W. Jansen, Professor of Economics and Director of the Private Enterprise Research Center, Texas A&M University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.