Sunday, June 11, 2023

Scientists warned about climate change in 1965. Nothing was done.

The long-awaited mission that could transform our understanding of Mars.

A next-generation instrument on a delayed Martian rover may be the key to answering the question of life on the Red Planet

By Carmen Drahl

March 17, 2022, was a rough day for Jorge Vago. A planetary physicist, Vago heads science for part of the European Space Agency’s ExoMars program. His team was mere months from launching Europe’s first Mars rover — a goal they had been working toward for nearly two decades. But on that day, ESA suspended ties with Russia’s space agency over the invasion of Ukraine. The launch had been planned for Kazakhstan’s Baikonur Cosmodrome, which is leased to Russia.

“They told us we had to call the whole thing off,” Vago says. “We were all grieving.”

It was a painful setback for the beleaguered Rosalind Franklin rover, originally approved in 2005. Budget woes, partner switches, technical issues and the Covid-19 pandemic had all, in turn, caused previous delays. And now, a war. “I’ve spent most of my career trying to get this thing off the ground,” Vago says. Complicating things further, the mission included a Russian-made lander and instruments, which the member states of ESA would need funding to replace. They considered many options, including simply putting the unused rover in a museum. But then, in November, came a lifeline, when European research ministers pledged 360 million euros to cover mission expenses, including replacing Russian components.

When the rover finally does, hopefully, blast off in 2028, it will carry a suite of advanced instruments — but one in particular could make a huge scientific impact. Designed to analyze any carbon-containing material found underneath Mars’s surface, the rover’s next-generation mass spectrometer is the linchpin of a strategy to finally answer the most burning question about the Red Planet: Is there evidence of past or present life?

“There are a lot of different ways that you can search for life,” says analytical chemist Marshall Seaton, a NASA postdoctoral program fellow at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and coauthor of a paper on planetary analysis in the Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry. Perhaps the most obvious and direct route is simply looking for fossilized microbes. But nonliving chemistry can create deceptively lifelike structures. Instead, the mass spectrometer will help scientists look for molecular patterns that are unlikely to be formed in the absence of living biology.

Hunting for the patterns of life, instead of structures or specific molecules, has an added benefit in an extraterrestrial environment, Seaton says. “It allows us to not only look for life as we know it, but for life as we don’t know it.”

Packing for Mars

At NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center outside Washington, DC, planetary scientist William Brinckerhoff shows off a prototype of the rover’s mass spectrometer, known as the Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer, or MOMA. Roughly the size of a carry-on suitcase, the instrument is a labyrinth of wires and metal. “It’s really a workhorse,” Brinkerhoff says as his colleague, planetary scientist Xiang Li, adjusts screws on the prototype before demonstrating a carousel that holds samples.

This working prototype is used to analyze organic molecules in Mars-like soils on Earth. And once the real MOMA gets to Mars, approximately in 2030, Brinckerhoff and his colleagues will use the prototype — as well as a pristine copy kept in a Mars-like environment at NASA — to test tweaks to experimental protocols, troubleshoot issues that come up during the mission and facilitate interpretation of Mars data.

This latest mass spectrometer can trace its roots back nearly 50 years, to the first mission that studied Martian soil. For the twin 1976 Viking landers, engineers miniaturized room-size mass spectrometers to roughly the footprint of today’s desktop printers. The instruments were also on board the 2008 Phoenix lander, the 2012 Curiosity rover and later Mars orbiters from China, India and the US.

Anyone visiting Brinckerhoff’s prototype must first pass a display case with a dismantled copy of the Viking instrument, on loan from the Smithsonian Institution. “This is like a national treasure,” Brinckerhoff says, enthusiastically pointing out components.

Mass spectrometers are indispensable tools that are used for analytical chemistry in laboratories and other facilities worldwide. TSA agents use them to test luggage for explosives at the airport. EPA scientists use them to test drinking water for contaminants. And drugmakers use them to determine chemical structures of potential new medications.

Many kinds of mass spectrometers exist, but each “is a three-part instrument,” explains Devin Swiner, an analytical chemist at the pharmaceutical company Merck. First, the instrument vaporizes molecules into the gas phase, and also gives them an electrical charge. These charged, or ionized, gas molecules can then be manipulated with electric or magnetic fields so they’ll move through the instrument.

Second, the instrument sorts ions by a measurement that scientists can relate to molecular weight, so they can determine the number and type of atoms a molecule contains. Third, the instrument records all the “weights” in a sample along with their relative abundance.

With MOMA aboard, the Rosalind Franklin rover will land at a Martian site that roughly 4 billion years ago likely had water, a crucial ingredient for ancient life. The rover’s cameras and other instruments will help to select samples and provide context about their environment. A drill will retrieve ancient samples from as deep as two meters. Scientists hypothesize that’s far enough, Vago says, to be shielded from cosmic radiation on Mars that breaks up molecules “like a million little knives.”

Space-bound mass spectrometers must be rugged and lightweight. A mass spectrometer with MOMA’s capabilities would normally occupy multiple workbenches, but it’s been shrunk substantially. “To be able to take something that can be as big as a room to the size of like a toaster or a small suitcase and send it into space is a very huge deal,” Swiner says.

The look of life

MOMA will help scientists look for telltale signs of life on Mars by sifting through molecules in search of patterns that are unlikely to be formed any other way. For instance, lipids — compounds that include building blocks of cell membranes — have a preponderance of even numbers of carbon atoms in nearly all living things, while nonliving chemistry produces a more equal mix of even and odd numbers of carbon atoms. Finding a set of lipids with carbon atoms that are multiples of a number — rather than a random assortment — is a potential signature of life.

Similarly, amino acids — the building blocks of proteins — can be created either by life or by non-biological chemistry. They come in two forms that are mirror images of each other but are otherwise identical, like left and right hands. On Earth, life overwhelmingly contains only left-handed amino acids. Nonliving chemistry makes both left- and right-handed varieties. In other words, a large excess of either left- or right-handed amino acids is more lifelike than a more even mixture.

More generally, scientists think that chemical distributions similar to these would be indicative of life even if the molecules exhibiting the patterns don’t exist in Earth biochemistry.

Previous Mars missions that included mass spectrometers ran into problems that hampered their ability to identify signs of life. Scientists took those hard-earned lessons and designed MOMA to overcome those hurdles, including one of the most troubling ones: the notorious molecule destroyer, perchlorate. Perchlorate, which also turns up in extreme Earth environments like South America’s Atacama Desert, can degrade organic molecules at high temperatures, obscuring potential signs of life.

In 2008, the Mars Phoenix lander discovered perchlorate ions in Mars soil. Two other missions, the Viking lander and the Curiosity rover, detected chlorinated hydrocarbons — possible byproducts of perchlorate reacting with Martian molecules in the high-temperature ovens of their mass spectrometers. This meant that perchlorate may have obscured any evidence of organic molecules that could indicate life.

MOMA cleverly circumvents the perchlorate problem with an ultraviolet laser. The laser vaporizes and ionizes samples in one go, with pulses of light lasting under two nanoseconds — too quick for perchlorate reactions to occur.

The laser has another benefit: It leaves molecules largely intact when giving them a charge to create ions. Viking and Curiosity generated ions by bombarding them with electrons. Those collisions didn’t preserve weak chemical bonds that can be important for determining the structures of molecules in a sample, whereas the laser keeps molecule fragmentation to a minimum. MOMA can then sort those relatively intact ions and deliberately fragment a single ion of interest in isolation, something neither Viking nor Curiosity could do. By analyzing the resulting puzzle pieces of that ion, it’s possible to determine the chemical structure of the original molecule from the Martian sample and thus identify what it is.

It will be the first time this laser technique goes to Mars, but tests on Earth suggest it will work. The prototype found traces of organic molecules even in the presence of more perchlorate than Phoenix detected in Martian soil, Brinckerhoff says. And in Mars-like samples collected in Yellowstone National Park, it detected lipids and other molecules that are more complex than ones picked up on previous Mars missions.

MOMA, like its predecessors, also has high-temperature ovens and scientists can still opt to use these instead of the laser to vaporize samples. If the laser turns up hints of amino acids, for instance, the oven option could provide information the laser cannot. When in oven mode, MOMA uses three chemical reagents that stabilize molecules to facilitate mass spectrometry. One of these, which has never before been used on Mars, is there to tell apart left- and right-handed amino acids, enabling it to make a case for living or nonliving origins in a way that prior missions could not.

MOMA won’t be the last word on whether life ever existed on Mars. Even the most tantalizing results would have to be confirmed by repeated experiments and lines of evidence from the rover’s other instruments, Vago says. Some confirmatory work also could take place through other missions or even someday from analysis of Mars samples brought back to Earth. “We will need to build a case, because otherwise nobody’s going to believe us,” Vago says.

The international team of scientists that has been working on the mission knows what they need to build that case, but until the Rosalind Franklin Rover lands on the Red Planet’s surface, they can’t get started. All of those scientists shared the disappointment in March 2022 of seeing the long-stalled mission delayed once again.

But for Brinckerhoff, that disappointment is tempered with excitement: After all, the mission is still alive. “This thing is the best of all of us,” he says, “and just to see it operate on Mars is going to be career catharsis.”

Carmen Drahl is a freelance journalist and editor based in Washington, DC. Find her portfolio at carmendrahl.com and follow her on Twitter or Mastodon @carmendrahl.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews.

Dealing with rats, and their health, in America’s ‘rattiest’ city.

OPINION: A study in Chicago found that rodents surviving poisoning are more likely to carry disease. Good pest control needs to take such things into account.

By Maureen Murray

This winter, I had the not-so-glamorous job of collecting organ samples from trapped rats in Chicago’s alleys. Normally a dead rat is not particularly attractive, but one caught my eye. Its stomach was a bright robin’s egg blue: a sure sign of teal-dyed rat poison.

Rat poisons (also called rodenticides) are a common way for people to control rats in cities around the world. Despite their ubiquity, rodenticides are becoming more controversial because they can accidentally kill pets or predators that eat the poison or the poisoned rats. In recent years, several states, including California and Massachusetts, have passed bills restricting the use of rodenticides in an effort to conserve wildlife.

Our work has also thrown up another, unanticipated problem: The poisoned rats we sampled that managed to survive the experience were three times more likely to be infected with leptospirosis, the world’s most widely distributed zoonotic (animal-to-human) disease.

I have been leading the Chicago Rat Project since 2018. Our city is famous for its skyline and lakefront but also for rodents: It has been dubbed the “rattiest city in America” for the past eight consecutive years, based on the number of complaints the city gets about rats.

We study how rats interact with people, wildlife and the environment to better understand public health risks from rats and improve their management. We do this using a holistic approach known as One Health, which looks at all aspects of health and the interconnections between the health of people, animals and the environment. Academic and public interest in One Health has increased dramatically since the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly because it can help to find win-win outcomes that protect both the environment and human well-being at the same time.

Rats can carry dozens of diseases transmissible to people. Leptospirosis, found in rat urine, causes fever, pain and kidney failure, and can be fatal if left untreated. Considered the most widely distributed zoonotic disease, leptospirosis is more common in tropical areas prone to flooding. Although the disease is rarer in the US, urban residents have died of leptospirosis after rat infestations, and it is becoming more common in domestic dogs. In addition, rat feces can contain salmonella (bacteria commonly known for food poisoning) and MRSA (“superbugs” that have become resistant to antibiotics). Rat bites can convey rat bite fever, and rat fleas can (but rarely) transmit the plague.

Our group has studied all different aspects of human-rat interactions. During the Covid-19 stay-at-home orders, for example, we found that rats made Chicago residents feel unsafe using their yards and patios, which at the time were so important for socializing and recreating. In our city, lower-income residents and residents of color are more likely to notice rat urine and feces inside their homes. Unsurprisingly, Chicago alleys with more accessible garbage have higher numbers of rats.

One striking finding from our group, gleaned from a study of 99 rats trapped and tested in 2018, was that rats that survived poisoning were three times more likely to carry leptospirosis than rats never exposed to poison. The dramatic difference in infection prevalence was surprising but mirrors other studies showing that predators exposed to rat poison are more likely to have parasites, likely because these compounds affect their immune systems.

Surprisingly, we also found that rats in some richer neighborhoods are more likely to carry leptospirosis — maybe because the larger and older estates in Chicago tend to have more standing water where leptospira bacteria can thrive. Affluent residents may also be more likely to hire pest professionals who use rodenticides. Rats are not “only” a problem associated with poverty.

In 2021, we surveyed nearly 700 people across Chicago about rats. Sadly, only 30 percent of our survey respondents even knew that rats can carry leptospirosis. Knowing the risks might encourage more people to use gloves and bleach when cleaning up rat urine.

We also found that residents are less likely to report their rats (and thus less likely to receive free rat abatement from the city) if they don’t believe the city will take their complaints seriously. Underserved and marginalized communities, already more likely to have rat waste in their homes, are less likely to think anyone well help them with their rats. This compounds existing issues with health equity.

So, what should be done? The most important step is to cut off the endless rat buffet that is garbage. New York City recently passed a law saying residents have to put their garbage out much later the night before pickup, for example, and they launched a municipal composting program because of rats. These are steps in the right direction.

Limiting the use of rat poison — for example by licensed professionals only — would help to prevent its inadvertent effects on rats and other wildlife. More intensive restrictions, allowing only “essential services” such as hospitals and food production to buy and use anticoagulant rodenticides, were recently implemented in British Columbia, Canada.

Effective rat management requires more than just an understanding of how to efficiently kill rats. It’s also about changing human behavior to stop rats from thriving, or from getting sick, or from entering homes; and teaching people how to report and deal with rats and rat waste. People, rats and other urban wildlife are all connected and our approach to rodent control must acknowledge these connections.

Maureen Murray is a wildlife disease ecologist at Lincoln Park Zoo’s Urban Wildlife Institute in Chicago.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews.

A Delicious Dip for Dad

Make it all about dad and celebrate Father’s Day with a table full of food to enjoy with family. Serving up something mouthwatering and delicious will have him coming back for another plate.

Try this Cheesy Pepperoni Dip to start dinner off with an appetizing kick. With creamy cheese, peppers and savory pepperoni, it’s a perfect way to hold everyone over before a stellar meal.

With a funny card, a bear hug and an appetizer like this, you can be on your way to a loving Father’s Day celebration.

Find more appetizer recipes at Culinary.net.

Watch video to see how to make this recipe!

Cheesy Pepperoni Dip

Recipe adapted from thepioneerwoman.com

Servings: 6-8

- 1 tablespoon vegetable oil

- 1 white onion, diced

- 1 can green chiles, diced

- 3/4 can diced tomatoes with green chiles

- 1 block (16 ounces) cheese, cubed

- 8 ounces cheddar cheese, shredded

- 4 ounces mozzarella cheese, finely shredded

- 1 jalapeno, diced

- 3/4 cup pepperoni, chopped

- 1 baguette

- butter

- Heat oven to 375 F.

- In skillet over medium heat, heat oil. Add onion and cook, stirring until softened, about 5 minutes. Add chiles and tomatoes; simmer.

- Reduce heat and stir in cubed cheese until smooth. Turn off heat; stir in cheddar and mozzarella until melted. Stir in jalapeno and half the pepperoni.

- Garnish with remaining pepperoni.

- Slice baguette into 1/2-inch slices. Place on baking sheet. Add butter to tops of slices. Toast in oven until tops are golden brown. Serve with dip.

Culinary.net

Five reasons Adam Smith remains Britain’s most important economist, 300 years on

Anna Plassart, The Open University

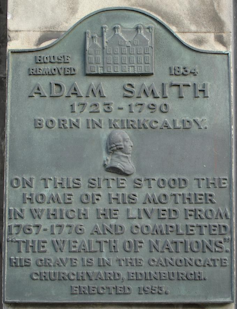

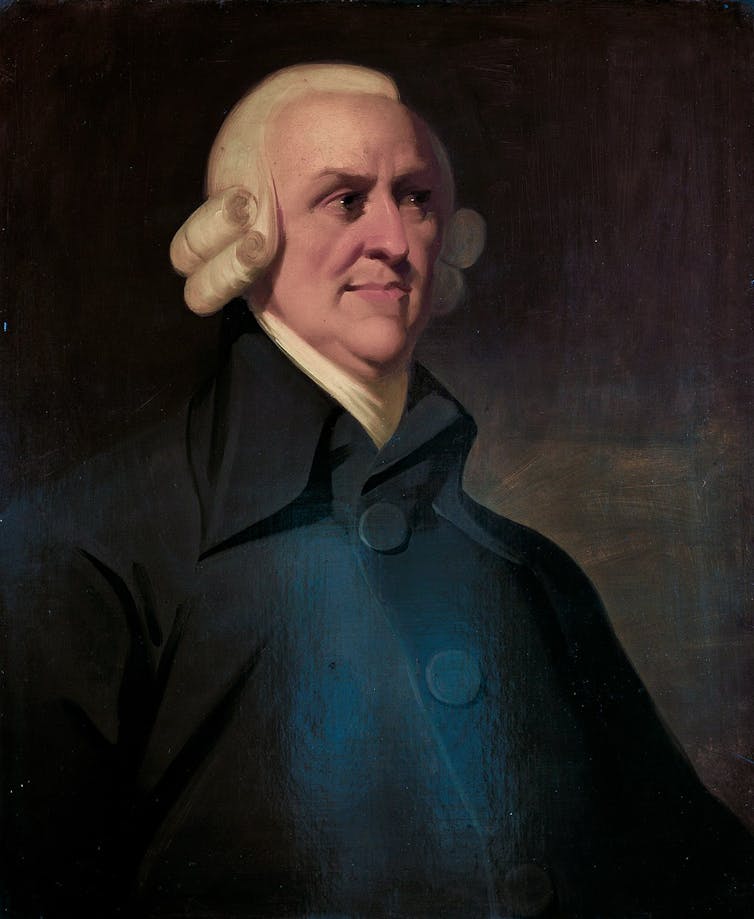

June 5 2023 marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Adam Smith, the 18th-century British economist widely hailed as the father of modern economics.

Born in Kirkcaldy, on the east coast of Scotland, Smith studied at the University of Glasgow and at Balliol College, Oxford (which he didn’t think highly of), before becoming a professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow. He was a quiet, unassuming man, only travelling when he accompanied a student on a tour of Europe in the 1760s. He died in Edinburgh in 1790.

Despite living an uneventful life, Smith is considered a central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment. His book Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, remains one of the most influential books ever written – second only to Karl Marx’s Das Kapital as the most cited work of classical economics of all time.

As my research shows, Smith is much more than the “father of economics”. He was a philosopher, a historian, and a political theorist. His life work was dedicated to working out the moral, social and political consequences – both good and bad – of the emerging capitalist and industrial economy in late 18th-century Britain. Here are five reasons why he remains Britain’s most important economist.

1. He invented fundamental economic concepts

Among the concepts Smith came up with – or helped to popularise – are productivity, free markets and the division of labour. His use of “the invisible hand” to describe the unseen mechanisms that regulate the market economy remains a central metaphor in contemporary economic thinking.

In the 19th century, economists inspired by Smith, including David Ricardo, laid the foundations of economics as the discipline we know today, by formalising economic reasoning in mathematical language. Smith’s innovative discussion of the rules of supply and demand anticipated the economic model of general equilibrium. His theory of economic growth also inspired later economists such as John Maynard Keynes to develop the notion of gross domestic product.

2. He has a cult following

Smith was already famous in his lifetime, even before he published Wealth of Nations. As a professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow between 1753 and 1763, his reputation attracted students from as far away as Russia.

However, in the 20th century, he became something of a hero for proponents of free markets. An influential thinktank founded in the 1970s, the Adam Smith Institute – dedicated to the pursuit of economic liberalism – bears his name. And as prime minister, Margaret Thatcher supposedly carried a copy of Wealth of Nations in her handbag.

Smith is widely celebrated –- often by people who haven’t read all his works –- as a prophet of individualism and neoliberalism. People see him as the man who foresaw the rise of industrial capitalism and provided definitive arguments against the idea of government interference. This, however, is a caricature of his writings.

Wealth of Nations was not a celebration of individualism. Smith was all too aware of the dangers and drawbacks of unbridled capitalism. In fact, he argued that governmental intervention was needed to keep economic inequalities in check. He also advocated breaking up monopolies, providing public works such as roads and bridges, and educating the middle classes.

3. He was the first Scot ever to appear on an English banknote

Between 2007 and 2020, Smith featured on English £20 banknotes. He was a proud Scotsman, a Kirkaldy native who spent his formative years in Glasgow.

Following Scotland’s 1707 union with England, Glasgow was asserting its place as a wealthy city of merchants. The city was benefiting from access to Britain’s growing trade empire, and by the 1740s it had become the centre of a thriving trading network with North America and the Caribbean.

At the University of Glasgow, Smith taught the sons of wealthy sugar and tobacco merchants and slave-labour plantation owners. They dominated local politics, invested their money in shipping and new industrial development, and were rebuilding Glasgow into an imposing city of stone.

4. He was a polymath

In his Glasgow classes, Smith lectured on moral philosophy, a broad humanities subject, which in 18th-century Scotland included topics as varied as morals, politics, religion, economics, jurisprudence and history.

He reworked some of these university lectures into a successful book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Published in 1759, this made him a household name throughout Europe.

Today, the book is mostly remembered by historians. But Smith believed his main achievement was teaching young Scots how to live a good, ethical life. Toward the end of his life, he wrote to the principal of the University of Glasgow that his 13 years as a professor of moral philosophy had been “the happiest and most honourable period” of his life.

5. His legacy is controversial

Smith’s economic theories have inspired a long line of free-market economists, but they also influenced Marx’s critique of capitalism. Marx admired Smith’s attempts to analyse the new modes of production that were emerging in early industrial Britain, as well as his innovative theory that wealth was related to labour.

Even today, Smith’s legacy is claimed both by neoliberals (who emphasise his defence of free trade) and by leftwingers (who emphasise his views on the pitfalls of capitalist economies). But Smith would have been puzzled by modern attempts to classify him as either of the right or the left. He was merely studying the changing world in which he lived: an early industrial society that was increasingly engaged in colonialism and global trade. It is time to reclaim Smith’s legacy from economists and to celebrate him as an astute observer of Europe’s emerging modernity.

Anna Plassart, Senior Lecturer in History, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Never mind Cleopatra – what about the forgotten queens of ancient Nubia?

Jada Pinkett Smith’s new Netflix documentary series on Cleopatra aims to spotlight powerful African queens. “We don’t often get to see or hear stories about Black queens, and that was really important for me, as well as for my daughter, and just for my community to be able to know those stories because there are tons of them,” the Hollywood star and producer told a Netflix interviewer.

The show casts a biracial Black British actress as the famed queen, whose race has stirred debate for decades. Cleopatra descended from an ancient Greek-Macedonian ruling dynasty known as the Ptolemies, but some speculate that her mother may have been an Indigenous Egyptian. In the trailer, Black classics scholar Shelley Haley recalls her grandmother telling her, “I don’t care what they tell you in school, Cleopatra was Black.”

These ideas provoked commentary and even outrage in Egypt, Cleopatra’s birthplace. Some of the reactions have been unabashedly racist, mocking the actress’s curly hair and skin color.

Egyptian archaeologists like Monica Hanna have criticized this racism. Yet they also caution that projecting modern American racial categories onto Egypt’s ancient past is inaccurate. At worst, critics argue, U.S. discussions about Cleopatra’s identity overlook Egyptians entirely.

In Western media, she is commonly depicted as white – most famously, perhaps, by screen icon Elizabeth Taylor. Yet claims by American Afrocentrists that current-day Egyptians are descendants of “Arab invaders” also ignore the complicated histories that characterize this diverse part of the world.

Some U.S. scholars counter that ultimately what matters is to “recognize Cleopatra as culturally Black,” representing a long history of oppressing Black women. Portraying Cleopatra with a Black actress was a “political act,” as the show’s director put it.

Ironically, however, the show misses an opportunity to educate both American and Egyptian audiences about the unambiguously Black queens of ancient Nubia, a civilization whose history is intertwined with Egypt’s. As an anthropologist of Egypt who has Nubian heritage, I research how the stories of these queens continue to inspire Nubians, who creatively retell them for new generations today.

The one-eyed queen

Nubians in modern Egypt once lived mainly along the Nile but lost their villages when the Aswan High Dam was built in the 1960s. Today, members of the minority group live alongside other Egyptians all over the country, as well as in a resettlement district near the southern city of Aswan.

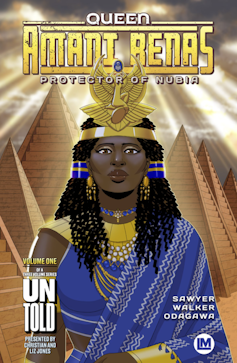

Growing up in Cairo’s Nubian community, we children didn’t hear about Cleopatra, but about Amanirenas: a warrior queen who ruled the Kingdom of Kush during the first century B.C.E. Queens in that ancient kingdom, encompassing what is now southern Egypt and northern Sudan, were referred to as “kandake” – the root of the English name “Candace.”

Like Cleopatra, Amanirenas knew Roman generals up close. But while Cleopatra romanced them – strategically – Amanirenas fought them. She led an army up the Nile about 25 B.C.E. to wage battle against Roman conquerors encroaching on her kingdom.

My own favorite part of this story of Indigenous struggle against foreign imperialism involves what can only be characterized as a power move. After beating back the invading Romans, Queen Amanirenas brought back the bronze head of a statue of the emperor Augustus and had it buried under a temple doorway. Each time they entered the temple, her people could literally walk over a symbol of Roman power.

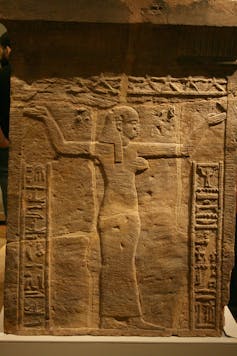

That colorful tidbit illustrates those queens’ determination to defend their autonomy and territory. Amanirenas personally engaged in combat and earned the moniker “the one-eyed queen,” according to an ancient chronicler of the Roman Empire named Strabo. The kandakes were also spiritual leaders and patrons of the arts, and they supported the construction of grand monuments and temples, including pyramids.

Interwoven cultures and histories

When people today say “Nubia,” they are often referring to the Kingdom of Kush, one of several empires that emerged in ancient Nubia. Archaeologists have recently started to bring Kush to broader public attention, arguing that its achievements deserve as much attention as ancient Egypt’s.

Indeed, those two civilizations are entwined. Kushite royals adapted many Egyptian cultural and religious practices to their own ends. What’s more, a Kushite dynasty ruled Egypt itself for close to a century.

Contemporary Nubian heritage reflects that historical complexity and richness. While their traditions and languages remain distinctive, Nubians have been intermarrying with other communities in Egypt for generations. Nubians like my mother are proudly Egyptian, yet hurtful stereotypes persist.

Today, some Black Americans embrace Cleopatra as a powerful symbol of Black pride. But the idea of ancient Nubia as a powerful African civilization also plays a symbolic role in contemporary Black culture, inspiring images in everything from cosmetics to comics.

Egyptian voices

Researchers do argue about Cleopatra’s heritage. U.S. conversations about her, however, sometimes reveal more about Western racial politics than about Egyptian history.

In the 19th century, for example, Western interest in ancient Egypt took off amid colonization – a fascination called “Egyptomania.” Americans’ fixation with the ancient civilization reflected their own culture’s anxieties about race in the decades after slavery was abolished, as scholar Scott Trafton has argued.

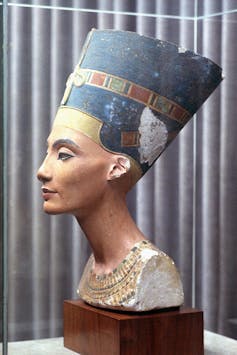

A century later, a 1990s advertisement for a pale-colored doll of queen Nefertiti sparked debate in the U.S. about how to represent her race.

Nefertiti’s bust – one of the most famous artifacts from ancient Egypt – is on display at a German museum. Egypt has called for the artifact’s return for close to a hundred years, to no avail. Even Hitler took a personal interest in the bust, declaring that he “will not renounce the queen’s head,” according to archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley.

Even today, contemporary Egyptian perspectives are almost absent in Western depictions of ancient Egypt. Only one Egyptian scholar is interviewed in the new Netflix series’ four episodes, as he himself notes, and he is employed not by an Egyptian university, but by a British one.

For many Egyptians, this lack of representation rehashes troubling colonial dynamics about who is considered an “expert” about their past. The Netflix series “was made and produced without the involvement of the owners of this history,” argues the Egyptian journalist Sara Khorshed in a review of the series.

To be sure, there is anti-Black bias in Egyptian culture, and some of the social media reaction has been slur-filled and racist. Educating people about the stories of Nubian queens like Amarinenas might be a way to encourage a more inclusive understanding of who is Egyptian.

Yet I believe Egyptians’ frustrations about portrayals of Cleopatra also reflect long-standing concerns that their own understandings of their past are not taken seriously.

That includes Black Egyptians, like my mother. When I asked her if she planned to see the Cleopatra series, she shrugged. She already knows that queen’s story well from its many portrayals on screen, whether in Hollywood films or Egyptian ones.

“I will wait for the series on Amanirenas,” she said.

Yasmin Moll, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Thursday, June 8, 2023

Aztec and Maya civilizations are household names – but it’s the Olmecs who are the ‘mother culture’ of ancient Mesoamerica

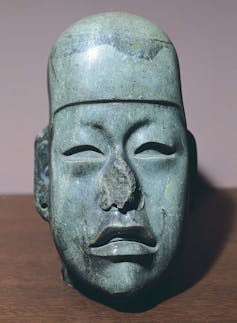

An extremely important 1-ton sculpture, sometimes referred to by archaeologists as an “Earth Monster” or Monument 9, was repatriated to Mexico from a private collection in Colorado in May 2023, according to an announcement from Mexico’s Consul General in New York. The monument features the head of a front-facing creature with a gaping mouth: a supernatural being that represented the living, animate earth to an ancient culture in Central America and Mexico.

This sculpture was reportedly found at the base of a hill at Chalcatzingo, an archaeological site some 80 miles (130 kilometers) south of Mexico City, and dates to roughly 600 B.C. Chalcatzingo is closely related to Olmec culture, one of the earliest in ancient Mesoamerica.

I am an archaeologist specializing in Mesoamerica: an area that encompassed present-day southern Mexico, parts of Costa Rica and all of Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua. I have visited Chalcatzingo many times while researching the development of this rich cultural region.

Many scholars regard the Olmec as the “mother culture” of ancient Mesoamerica, a civilization where particular types of monumental architecture, sculpture and gods originated. Among the later Maya, for example, the gods of wind, rain and corn – or more precisely, maize – are clearly derived from the earlier Olmec culture.

Elaborate art

The Olmec heartland was in what are now the Mexican states of Tabasco and southern Veracruz, along the southern coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Much of their influence was based on economic wealth from corn.

Of Olmec art that has survived the centuries, their carved heads are particularly striking and well known. By 1000 B.C., Olmec sculptors at San Lorenzo, Mexico, had fashioned no fewer than 10 colossal heads, all over 6 feet high. Archaeologists believe these are individualized portraits of rulers, each with their own specific headdress: depictions of specific people, which is quite rare in New World art.

The Olmecs were also masters in the carving of jade. I was involved in locating the original Olmec and Maya jadeite sources in highland eastern Guatemala, found in stone outcrops often located about 6,000 feet above sea level.

Artisans beginning around 900 B.C. carved life-size jade masks that almost look like molded plastic, but which must have been the result of a laborious process to grind and polish this extremely hard, dense stone.

Sacred system

All Olmec sculpture was created for a purpose, whether it be religious or political. In the case of Monument 9, it clearly pertains to the Earth, which in Mesoamerica was considered a sacred, living being.

The Olmecs existed at a time when maize agriculture had first developed, which stabilized and increased their economy – a transformative shift in the development of Mesoamerican civilization.

During this period, they developed an elaborate religious system that emphasized the sacredness of corn and rain, including a maize god. Quite frequently, this deity is depicted with an ear of corn emerging out of the center of his cleft head. In other cases, the head is sharply turned back, invoking growing corn. This form appears in Teopantecuantitlán, an archaeological site in highland Mexico, where there is a masonry court with four images of the Olmec maize god.

As a tall grass, corn needs a great deal of water to survive the summer, making rain all-important. Trying to please the rain god in return for rain was a vital part of Olmec religion.

The Olmec spread similar practices and beliefs across ancient Mexico and Guatemala, probably in part to engage other peoples more directly with their economic trade network. Rather than an empire of domination, the Olmec were a culture focused on agricultural abundance and wealth.

Sacred mountains were of extreme importance as well, as can be seen at Chalcatzingo and at a hill called Cerro El Manatí, located very close to the site at San Lorenzo. At this hill, there is a perennial spring with sweet freshwater that fills a pool below at the base. In this pool, the Olmec offered a huge amount of valued material, including rubber balls for ritual sport, as well as many jadeite axes. According to two scholars of Mesoamerica, Ponciano Ortiz and María del Carmen Rodríguez, this is the first clear example of a sacred mountain of abundance, which persists in Mesoamerican belief and ritual to this day.

Earth Monster’s home

Far to the west of the Olmec heartland, in the Mexican state of Morelos, is Cerro Chalcatzingo, the site where the Earth Monster monument originated. Here, the Olmec focus on the mountain as a provider of wealth and sustenance, portrayed in several sculptures as a cave.

Even before Olmec times, the idea of fertile caves was shown as a four-lobed motif resembling a flower – an important symbol that continued even into the 16th century with the Aztec.

The most famous Olmec bedrock carving at Chalcatzingo is called Monument 1 and features a woman in profile – probably a goddess – seated within the cave. This carving is directly above where rainwater pours down from the top of the mountain. Below are what archaeologists call “cupules”: cuplike holes carved in bedrock directly below to receive this water, and collected by priests and pilgrims. On the opposite side of the hill is another rock carving featuring the same cave in profile, facing Monument 1.

Sadly, Monument 9, which was recently returned to Mexico, was looted from the site, so its original context is unknown. In archaeology, it is important to understand not only when an object was made and who created it, but where it was placed. Nonetheless, Monument 9 portrays the same cave as two other sculptures at the site, which are carved directly into the rock surface of the mountain.

Monument 9 is significant, as it denotes the central Earth Monster cave, and unlike the other two Olmec carvings, it is face-on rather than rendered in profile. It probably was placed against a mound with its open mouth leading to a chamber inside, symbolizing a portal to the underworld.

That this highly sacred object is back in Mexico is of utmost importance for Indigenous Mexicans. To its creators, Monument 9 likely represented the source of life and abundance, as well as sacred rituals associated with them – ideas and practices that pervaded subsequent Mesoamerican civilizations.

Karl Taube, Distinguished Professor of Anthropology, University of California, Riverside

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.