The seizures started when Samantha Gundel was just four months old. By her first birthday, she was taking a cocktail of three different anticonvulsant medicines. A vicious cycle of recurrent pneumonia, spurred on by seizure-induced inhalation of regurgitated food, landed the young toddler in and out of the hospital near her Westchester County home in New York State.

Genetic testing soon confirmed her doctors’ suspicions: Samantha, now age 4, has Dravet syndrome, an incurable form of epilepsy. Her brain was misfiring because of a mutation that is unlike those responsible for most genetic diseases; it’s a type that has long eluded the possibility of correction. Available drugs could help alleviate symptoms, but there was nothing that could address the root cause of her disease.

That’s because the mutation at the heart of Dravet creates a phenomenon known as haploinsufficiency, in which a person falls ill if they have only a single working copy of a gene. That lone gene simply can’t produce enough protein to serve its molecular purpose. In the case of Dravet, that means that electrical signaling between nerve cells gets thrown out of whack, leading to the kinds of neuronal shock waves that trigger seizures.

Most genes are not like this. Though the human genome contains two copies of almost every gene, one inherited from each parent, the body can generally do fine with just one.

Not so for genes such as SCN1A, the main culprit behind Dravet. For SCN1A and hundreds of other known genes like it, there’s a delicate balance of molecular activity that is needed to ensure proper function. Too little activity is a problem — and oftentimes, so is too much.

This Goldilocks paradigm partially explains why conventional gene therapy strategies are ill-suited to the task of haploinsufficiency correction. With therapies of this kind — several of which are now available to treat “recessive” genetic diseases such as the blood disorder beta thalassemia and a form of inherited vision loss — the amount of protein made by an introduced gene just needs to cross a minimum threshold to undo the disease process.

In those contexts, it’s not a problem if the added gene is overactive — there’s a floor, but no ceiling, to therapeutic protein levels. That is simply not the case with many dosage-sensitive diseases like Dravet, especially for brain disorders in which too much protein can overexcite neuronal activity, says Gopi Shanker, who served as chief scientific officer of Tevard Biosciences in Cambridge, Massachusetts, until earlier this year. “That’s what makes it more challenging,” he says.

Adding to the challenge: The special types of modified viruses that are used to ferry therapeutic genes into human cells can handle only so much extra DNA — and the genes at the heart of Dravet and many related haploinsufficiency disorders are much too big to fit inside of these delivery vehicles.

Overlooked no more

Faced with these technical and molecular hurdles, the biotechnology industry long ignored haploinsufficiencies. For more than 30 years, companies jostled to get a piece of the drug development action in other areas of rare genetic disease — for cystic fibrosis, say, or for hemophilia — but conditions like Dravet got short shrift. “It’s one of the most neglected classes of disorder,” says Navneet Matharu, cofounder and chief scientific officer of Regel Therapeutics, based in Berkeley, California, and Boston.

Not anymore. Thanks to new therapeutic ideas and a better understanding of disease processes, Regel, Tevard and a group of other biotech startups are taking aim at Dravet, with experimental treatments and technologies that they say should serve as testing grounds for going after haploinsufficiency diseases more broadly.

Currently, there’s little to offer patients with these maladies other than drugs to aid with symptom control, says Kenneth Myers, a pediatric neurologist at Montreal Children’s Hospital who cowrote an article about emerging therapies for Dravet and similar genetic epilepsies in the 2022 issue of the Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. But thanks to new advances, he says, “there’s a huge reason for optimism.”

Samantha, for one, now seems to have her disease under control because of a drug called STK-001; it is the first ever to be evaluated clinically that addresses the root cause of Dravet.

Between February and April 2022, doctors thrice inserted a long needle into the young girl’s lower spine and injected the investigational therapy, which is designed to bump up levels of the sodium-shuttling protein whose deficiency is responsible for Dravet. It seemed to work. For a time, Samantha lived nearly seizure-free — presumably because the increased protein levels helped correct electrical imbalances in her brain.

Conventional gene therapy strategies are ill-suited to the task of haploinsufficiency correction.

She went from epileptic attacks every 7 to 10 days, on average, to nothing for months on end. Her verbal skills improved, as did her physical capabilities. Her gait improved and her tremors disappeared.

Eventually, as the therapy wore off, Samantha began to backslide, with seizures returning every couple of weeks or so. But she started receiving additional doses of STK-001 under a new trial protocol in October 2022, and since then has experienced only two epileptic episodes over the span of six months. “It’s really pretty amazing,” says her mother, Jenni Barnao.

“Is it a cure? No.… But this is absolutely our best shot,” Barnao says. “There’s definitely something with this drug that’s very good. Her brain is just working better.”

Give a boost

The STK-001 treatment relies on the fact that the normal activity of genes is somewhat inefficient and wasteful. When genes get decoded into mRNA, the resulting sequences require further cutting and splicing before they’re mature and ready to serve as guides for making protein. But often, this process is sloppy and doesn’t result in usable product.

Which is where STK-001 comes in.

A kind of “antisense” therapy, STK-001 consists of short, synthetic pieces of RNA that are tailor-made to stick to part of the SCN1A gene transcript and, as a result, make productive cutting and splicing more efficient. The synthetic pieces glom on to mRNA from the one working version of the gene that people with Dravet have and help to ensure that unwanted bits of the mRNA sequence are spliced out, just as a movie editor might cut scenes that detract from a film’s story. As a result, more functional ion channel protein gets made than would otherwise happen.

Protein levels don’t get completely back to normal. According to mouse studies, there’s a 50 percent to 60 percent boost, not a full doubling of the relevant protein in the brain. But that bump seems to be enough to make a real impact on patients’ lives.

Stoke Therapeutics, the company in Bedford, Massachusetts, that is behind STK-001, reported at the American Epilepsy Society’s 2022 Annual Meeting that 20 of the first 27 Dravet patients to receive multiple doses of the therapy in early trials experienced reductions in seizure frequency. The greatest benefits were observed among young children like Samantha whose brains have accumulated less damage from years of debilitating seizures and abnormal cell function. Larger confirmatory trials that could lead to marketing approval are scheduled to begin next year.

Stoke is hardly alone in its quest to fix Dravet and haploinsufficiency disorders more generally. Several other biotech startups are nearing clinical trials with their own technological approaches to enhancing what working gene activity remains. Encoded Therapeutics, for example, will soon begin enrolling participants for a trial of its experimental Dravet therapy, ETX-001; it uses an engineered virus to deliver a protein that ramps up SCN1A gene activity so that many more mRNA copies are made of the single, functional gene.

And if any of these companies succeed in reversing the course of Dravet, their technologies could then be adapted to take on any comparable disease, says Orrin Devinsky, a neurologist at NYU Langone Health who works with several of the firms and is involved in Samantha’s care. “An effective therapy would provide a potential platform to address other haploinsufficiencies,” he says.

New targets, new tactics

Stoke will soon put that idea to the test.

Buoyed by the early promise of its Dravet therapeutic, the company developed a second drug candidate, STK-002, that similarly targets splicing to turn nonproductive gene transcripts into constructive ones. But in this case, it’s designed to tackle an inherited vision disorder known as autosomal dominant optic atrophy, caused by haploinsufficiency of a gene called OPA1. In this disease, a single working copy of OPA1 is not enough to sustain proper nerve signaling from the eyes to the brain.

Clinical evaluation of STK-002 is expected to start next year. Meanwhile, in partnership with Acadia Pharmaceuticals of San Diego, Stoke is also exploring treatments for Rett syndrome and SYNGAP1-related intellectual disability, both severe brain disorders caused by insufficient protein levels.

“There’s definitely something with this drug that’s very good. Her brain is just working better.”

Jenni BarnaoStoke’s splice-modulating approach flows naturally from the success of another antisense drug, Spinraza. Developed by Ionis Pharmaceuticals in collaboration with Biogen, Spinraza also works on splicing of mRNA transcripts to promote production of a missing protein. In 2016, it became the first therapy approved for treating a rare neuromuscular disorder called spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).

SMA is somewhat different, though. It isn’t a haploinsufficiency — it occurs when both gene copies are defective, not just one — but it’s an unusual disease from a genetics standpoint. Because of a quirk in the human genome, it turns out that people have a kind of backup gene that doesn’t normally function because its mRNA undergoes faulty splicing. With Spinraza acting as a guide to help the mRNA splice correctly, that backup gene can be made operational and do the job that the damaged gene copies can’t do.

Few diseases are like this. But Stoke’s scientific cofounders, molecular geneticist Adrian Krainer of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York (who helped to develop Spinraza) and his former postdoctoral researcher Isabel Aznarez, realized that there was a whole world of other ailments — haploinsufficiencies — for which this type of splice modulation could be beneficial.

Spinraza was the prototype. Stoke’s portfolio is full of the next-generation editions. “We brought it to the next level,” says Aznarez, who now serves as head of discovery research at Stoke.

Striking a balance

There was a time when Dravet researchers were more focused on traditional gene replacement therapies. They aimed to insert a working version of the SCN1A gene into the genome of a virus and then introduce the engineered virus into brain cells. The problems proved manifold, though.

For starters, the virus vehicles generally used in gene therapy strategies — adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) — are too small to hold all 6,030 of the DNA letters that constitute the SCN1A gene sequence.

Researchers tried a few potential workarounds. At University College London, for example, gene therapist Rajvinder Karda and her colleagues split the SCN1A gene in half and delivered both parts into mice in different virus carriers. And at the University of Toronto, neuroscientist David Hampson and his group tried introducing a smaller gene that would fit in a single AAV vector and compensate for the SCN1A deficiency in an indirect way.

But none of those efforts advanced past mouse experiments. And while it is technically feasible to deliver the entire SCN1A gene into cells if you use other kinds of viral vectors, as researchers at the University of Navarra in Spain showed in mice, those viruses are generally considered unsafe for use in people.

To get protein levels just right, scientists say, it is best to follow the cell’s own lead.

What is more, even if gene replacement could be made to work, there are many reasons to think it would not be ideal for diseases like Dravet in which the underlying defect is mediated by an imbalance of protein levels. The amount of protein produced by those kinds of gene therapies can be unpredictable, and so are the types of cells that end up manufacturing the proteins.

To get protein levels just right, scientists say, it is best to follow the cell’s own lead, tapping into the ways that it naturally produces the protein of interest only in certain tissues of the body, and then providing a therapeutic nudge to aid the process along.

CAMP4 Therapeutics, for example, is using antisense therapies, like Stoke. But instead of targeting the splicing of gene transcripts, CAMP4’s drugs are directed at regulatory molecules that act like rheostats to control how much of those transcripts are made in the first place. By blocking or stabilizing different regulatory molecules, the company claims it can ramp up the activity of target genes in a precise and tunable way.

“It’s basically teaching the body to do it a little bit better,” says Josh Mandel-Brehm, president and CEO of CAMP4, which is based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

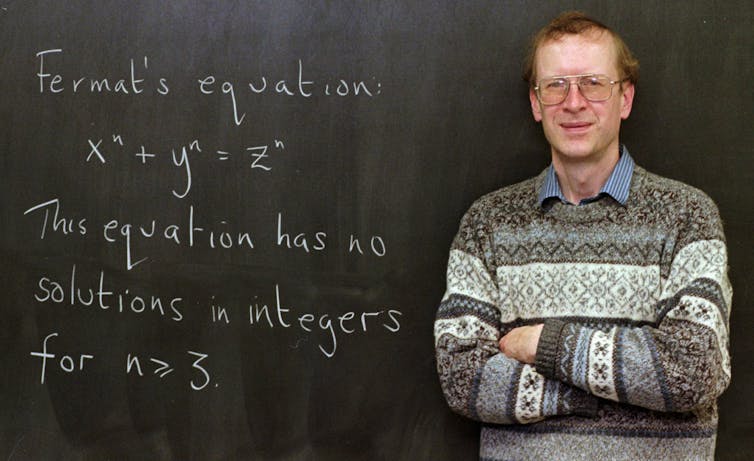

In theory, the gene-editing technology known as CRISPR could obviate the need for all of these therapeutic approaches. Gene editing allows you to perfectly correct a mistake in a gene — so one could edit a faulty DNA sequence to correct it and render kids with Dravet or some other haploinsufficiency disease as good as new.

But the technology is nowhere near ready for prime time. (Some of the first CRISPR therapies to be tested in children have failed to demonstrate much benefit.) Plus, any gene-correction therapy would have to be tailored to the unique nature of a given patient’s mutations — and there are more than 1,200 Dravet-causing mutations in the SCN1A gene alone.

That’s why Jeff Coller, an RNA biologist at Johns Hopkins University and a scientific cofounder of Tevard, prefers therapeutic strategies that can address all manner of disease-causing alterations in a gene of interest, as most companies are doing now. “Having a mutation-agnostic technology is a way of going after the entire cohort of patients,” he says.

“We’re open to any approach that would help our daughters.”

Daniel FischerTevard, whose mission is to “reverse” Dravet syndrome (the company’s name is Dravet spelled backward), is approaching this challenge in various ways. Some involve engineered versions of other RNAs that are key for protein production; known as “transfer” RNAs, they help to ferry amino acid building blocks to the growing protein strands. Others are intended to help bring beneficial regulatory molecules to sites of SCN1A gene activity.

But all of Tevard’s therapeutic candidates remain at least a year away from clinical testing, whereas STK-001 is in human trials today. So the company’s chief executive, Daniel Fischer — who, along with board chair and cofounder Warren Lammert, has a daughter affected by Dravet — is considering enrolling his child, now 13, in the Stoke trial rather than waiting for his own company’s efforts to bear fruit.

“We’re open to any approach that would help our daughters,” Fischer said over lunch last November at the company’s headquarters.

“And help people with Dravet generally,” added Lammert. “We’d love to see many of these things succeed.”

Editor’s note: This article was amended on April 14, 2023, to correct Gopi Shanker’s relationship with Tevard Biosciences. Shanker is Tevard’s former chief scientific officer; he is now chief scientific officer with Beam Therapeutics.