Weather forecasts have gotten quite good over the years, but their temperatures aren’t always spot on – and the result when they underplay extremes can be lethal. Even a 1-degree difference in a forecast’s accuracy can be the difference between life and death, our research shows.

As economists, we have studied how people use forecasts to manage weather risks. In a new working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, we looked at how human survival depends on the accuracy of temperature forecasts, particularly during heat waves like large parts of the U.S. have been experiencing in recent days.

We found that when the forecasts underplayed the risk, even small forecast errors led to more deaths.

Our results also show that improving forecasts pays off. They suggest that making forecasts 50% more accurate would save 2,200 lives per year across the country and would have a net value that’s nearly twice the annual budget of the National Weather Service.

Forecasts that are too mild lead to more deaths

In the U.S. alone, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issues 1.5 million forecasts per year and collects around 76 billion weather observations that help it and private companies make better forecasts.

We examined data on every day’s deaths, weather and National Weather Service forecast in every U.S county from 2005 to 2017 to analyze the impact of those forecasts on human survival.

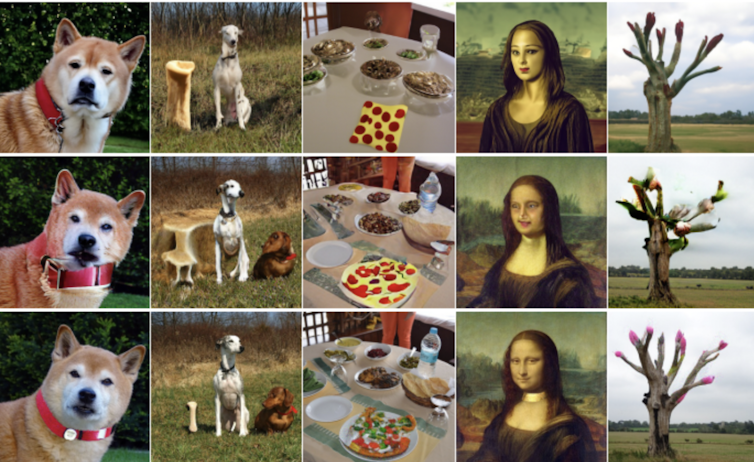

We then compared deaths in each county over the week following a day with accurate forecasts to deaths in the same county over the week following a day with inaccurate forecasts but the same weather. Because weather conditions were the same, any differences in mortality could be attributed to how people’s reactions to forecasts affected their chance of dying in that weather.

We found similar results when the forecast was wrong on hot days with temperatures above 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 Celsius) and on cold days with temperatures below freezing. Both summer days that were hotter than forecast and winter days that were colder had more deaths. Forecasts that went the other way and overestimated the summer heat or winter cold had little impact.

That doesn’t mean forecasters should exaggerate their forecasts, however. If people find that their forecasts are consistently off by a degree or two, they might change how they use forecasts or come to trust them less, leaving people at even higher risk.

People are paying attention

People do pay attention to forecasts and adjust their activities.

The American Time Use Survey, conducted continuously for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, shows what Americans across the country are doing on any given day. We found that on days when the forecast called for temperatures to be milder than they turned out to be – either cooler on a hot day or warmer on a cold day – people in the survey spent more time on leisure and less in home or work settings.

Electricity use also varies in sync with forecasts, suggesting that people’s use of air conditioning does not just respond to the weather outside but also depends on how they planned for the weather outside.

However, forecasts are not used equally across society. Deaths among racial minorities are less sensitive to forecast errors, we found. That could be due in part to having less flexibility to act on forecasts, or not having access to forecasts. We will dig into this difference in future work, as the answer determines how the National Weather Service can best reach everyone.

The value of better forecasts

It’s clear that people use forecasts to make decisions that can matter for life and death – when to go hiking, for example, or whether to encourage an elderly neighbor to go to a cooling center.

So, what is the value of accurate forecasts?

We combined our theoretical model with federal cost-benefit estimates of how people value improvements in their chances of survival. From those, we estimated people’s willingness to pay for better forecasts. That calculation accounts for the risk of dying from extreme weather and for the costs of using forecasts to reduce their risk of dying, such as the costs of altering work and play schedules or using electricity.

The result shows that 50% more accurate forecasts are worth at least US$2.1 billion per year based on the mortality benefits alone. In comparison, the 2022 budget of the National Weather Service was less than $1.3 billion.

Weather forecasts have gotten steadily better over the past decades. About 68% of the next-day temperature forecasts now have an error of less than 1.8 degrees. Our results suggest investing in improved forecast accuracy would probably be worth the cost.

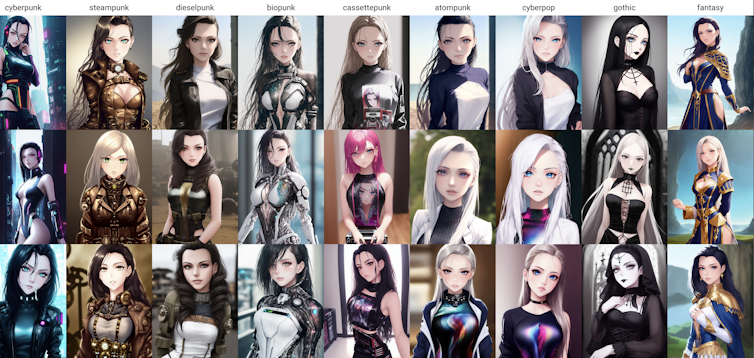

Past improvements have come from better models, better observations and better computers. Future improvements could come from similar channels or from applying recent innovations in machine learning and artificial intelligence to weather prediction and communication.

Climate change will increase the frequency of extremely hot days, which are especially important for human health and survival to forecast accurately. Climate change will make the weather weirder, but weird weather can do less harm when we can see it coming.

Derek Lemoine, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Arizona; Jeffrey Shrader, Assistant Professor of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University, and Laura Bakkensen, Associate Professor of Economics and Policy, University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Take stock of current inventory – Before you hit the stores, take inventory of items you already have at home or in the office to see what you truly need. Knowing what you already have on hand can help you avoid the temptation of stocking up on items you may not even need just because they were on sale. That 50-cent pack of crayons may be a good deal, but too many of those can add up, especially if you realize later you had the same item sitting unused in a closet or drawer at home.

Take stock of current inventory – Before you hit the stores, take inventory of items you already have at home or in the office to see what you truly need. Knowing what you already have on hand can help you avoid the temptation of stocking up on items you may not even need just because they were on sale. That 50-cent pack of crayons may be a good deal, but too many of those can add up, especially if you realize later you had the same item sitting unused in a closet or drawer at home.