Lots of them depend on fruit-eating birds and mammals to spread their seeds. But it’s debatable whether the animals — many in trouble themselves — can disperse seeds far and fast enough to keep pace with a warming world.

Haldre Rogers’ entry into ecology came via the sort of manmade calamity that scientists euphemistically call an “accidental experiment.”

She’d taken a job in 2002 on the Pacific island of Guam and the neighboring Mariana Islands to study the invasive brown tree snakes that were introduced to Guam, likely from a cargo ship, shortly after World War II. In the ensuing decades, these large snakes thrived, and many native animals were obliterated.

Rogers’ initial task was to track reported sightings on nearby islands. The job, she says, “gave me lots of time to just stare at trees, trying to see snakes. And I realized that, ‘Oh, there’s actually all of these differences between forests on Guam and forests on other islands.’”

And so, for her PhD, Rogers decided to address whether the snakes themselves had changed Guam’s trees and shrubs.

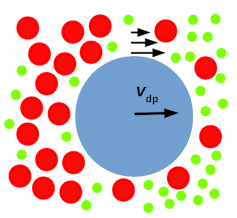

The potential link was this: Many trees and other plants rely on animals to disperse their seeds — and that’s often achieved through fruit. Like mini ecological Trojan horses, fruit evolved to be eaten, its pulp a nutritious lure to make an animal consume it and swallow a plant’s seeds, too.

The animal moves on. After a while, it defecates, depositing the swallowed seeds somewhere within its range. Oftentimes, those seeds emerge in what amount to little fertilizing clumps of manure.

Myriad factors will determine whether a seed ever becomes a mature plant. But by co-opting the wings, legs, guts and back ends of animals, rooted plants have evolved a way of scattering the embryonic forms of their offspring far and wide.

In Guam, forest trees had relied on seven main species of disperser — six birds and one bat — and the tree snakes decimated them. When Rogers arrived, only one bird disperser remained, and only in a limited range, and the bat population was down to about 50 individuals. “So, basically, no seed dispersal,” says Rogers, now an ecologist at Virginia Tech.

Across the island, fruits now just drop to the forest floor.

There are winners and losers among Guam’s plants, Rogers found. Some species that are less dependent on animals are thriving. But many native fruiting trees and shrubs are struggling. There is less mixing, and forests have a lower diversity of plant species as a result.

Particularly striking is what happens when a mature tree falls in the forest. Normally, Rogers says, a free-for-all ensues as masses of growing seedlings fight over the newly available light. On Guam, these gaps fill very slowly because seeds aren’t brought in. “When you lose a seed disperser,” Rogers says, “there’s nothing else that’s going to take over that role in the system.”

If this were simply an inadvertent experiment on one faraway island — confirming what ecologists have long hypothesized about plants’ reliance on frugivorous, or fruit-eating, animals — it would be a local misfortune. But with populations of wild animals plummeting worldwide, ecologists fear that, instead, it serves as a widespread warning.

In Madagascar, researchers recently showed that several endangered trees, including species of palm and baobab, produce seeds too large for any living animals to swallow and distribute. The giant lemurs and elephant birds that must once have distributed them are long extinct, rendering them “ghost fruit.”

In the Western United States and Mexico, as numbers of pinyon jays plummet, ecologists worry about the long-term persistence of piñon pines, whose seeds are cached and spread by these birds.

Examples like this exist all over the world.

But an even bigger issue is that plants probably need their seed-dispersing animals now more than ever. As temperatures quickly rise due to climate change, many plants will have to move to cooler locations to survive. However, research by seed-dispersal ecologists is suggesting that the world’s shrinking animal populations do not have the capacity to mediate these migrations.

“The world is changing so rapidly. Things have to respond in some way,” says Rogers. “Understanding movement is going to be hugely important.”

The right moves

Researchers estimate that over half the world’s seed-bearing plants rely on animal-mediated seed dispersal and that in tropical forests, the number is 75 percent or more. That reliance, Rogers says, takes various forms.

For example, as shown in Guam, fruit-eating animals serve an ongoing and vital maintenance function within a local population. Seeds dispersed randomly by animals can land in healthy new growing spots and ensure mixed ecosystems, whereas fruits that fall beneath their parents are competing with their siblings and are, quite literally, in their parents’ shadow.

Such fallen seeds have also lost the often-important step of passing through an animal’s gut. Digestion may wash away molecules that inhibit germination and it strips the seed of surrounding flesh that, if left in place, can promote the growth of fungi and other pathogens.

But as Rogers and colleagues described in the 2021 Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, another service will be important for surviving climate change: transporting seeds beyond their parents’ current range. As temperatures rise, plants will have to track — or follow — the movement of the climatic conditions to which they are adapted. Broadly speaking, that means moving north for Northern Hemisphere species and south for Southern Hemisphere species — or to higher altitudes.

Juan P. González-Varo, an ecologist at the University of Cadiz in Spain, explains that since average temperatures vary according to latitude — getting cooler farther from the equator — ecologists can calculate how quickly a species will need to move toward cooler climes to stay at the same average temperature, based on data about rates of global heating. The current estimate is 4.2 kilometers per decade — a significant range shift. And the rate of needed movement is greater for woody fruiting plants because they often take years or even decades to reach reproductive maturity, González-Varo says.

Ecologists are asking whether today’s animals populations will permit plants to achieve this.

González-Varo’s own work, for example, is focused on birds. He says that in the mid-2010s, when ecologists described how crucial plant migration would be in the future, authors of certain influential papers said that migratory birds are well-positioned to move seeds the necessary distances.

But although migratory birds do make lengthy journeys, seeds can pass through avian gastrointestinal tracts as quickly as 20 minutes after being swallowed. Will birds retain seeds long enough to carry them far enough?

Researchers examining the gut contents of migratory birds on the Atlantic’s Canary Islands did find seeds from the mainland some 170 kilometers away, indicating that long-range dispersal can happen. But González-Varo felt there was a problem and, in 2021, he and colleagues published work on European forests that confirmed his pessimism: Migrating birds are typically traveling in the wrong direction when they eat fruit.

The researchers gathered data on 949 examples of 46 bird species eating the fruit of 81 different plants. They observed that migrating birds tended to eat European fruits when they were heading south for winter, from colder to warmer climes. It’s the opposite direction from that needed to keep up with climate change. Only around one-third of the plant species studied, including plants such as holly, wild olives and ivy, produce fruit in the spring when the birds are heading north — a time that would help the species move to cooler latitudes.

So if migratory birds had been seen as the solution to plants tracking climate change, González-Varo says this study showed they are “a very partial solution.”

Rising temperatures, shorter distances

A huge simulation published in 2022 examined more closely the global capacity of all animals to move seeds around. The results were also concerning.

Ecologist Evan Fricke of MIT, Rogers and coauthors first built a database of every field study they could access in which researchers had quantified aspects of seed dispersal by animals. Which animals eat fruit from which plants? Do the animals swallow, strip, cache or destroy the seeds? How far do the animals take seeds? And in which instances do seeds produce new plants? The model was ultimately fed by data from around 18,000 animal-plant interactions.

Next, the team added data describing each animal and plant species; the team also included data on the natural geographic ranges of species, including estimates of where extinct species would live today had they not gone extinct.

Finally, they used machine learning to simulate the degree to which animals are distributing seeds across the globe today, and how declines in dispersers and their habitats are affecting seed movement.

The first thing to pop out of the model was a strong correlation between the size of an animal — especially mammals — and how far it disperses seeds. Typically, large mammals have large ranges and seeds take longer to pass through them. (Birds, Fricke says, mostly occupy quite small ranges when they’re not migrating.) That is a problem, because large mammals are far more likely than small ones to have been driven to extinction by people or to be heading in that direction.

Fricke’s team then looked at dispersals greater than 1 kilometer from parent plant’s range — the sort needed to shift plants’ ranges. Their model showed that extinctions and declines in habitat have vastly reduced the long-distance dispersal of seeds. “There have been really strong declines in long-distance seed dispersal as a result of the massive loss of big animals from the ecosystems,” says Fricke.

Whether it’s cave paintings in France or the fossil record, historical data show that large mammals were once widespread, constantly moving seeds long distances. “That helped deal with the climate changes that have happened in the last 10,000 years or so,” Fricke says. “But they’re no longer helping plants with climate change now, because they are either completely extinct or are restricted to really small areas within their former ranges.”

The team ran another simulation in which all currently endangered birds and mammals become extinct. Under this scenario, seed dispersal of more than 1 kilometer would further suffer, with some of the greatest losses occurring in Madagascar and Southeast Asia.

In short, Fricke says, as temperatures increase, seed movement is decreasing — right at the time when it’s needed most.

Dwindling dispersal

To complicate matters further, sometimes an animal species can stop dispersing seeds even when it’s still around and still eating fruit, says Kim McConkey, an ecologist affiliated with the UK’s University of Nottingham Malaysia campus who has observed the habits of many frugivorous creatures. Loss of predators is one cause. Without the fear of being snatched by, say, a fox or a hawk, rodents are less likely to carry seeds away from the plants where they found them. Noise and light pollution is another: It can deter seed dispersers from venturing into certain areas.

Reduced competition for food can also dramatically change dispersal patterns. On Guam, surviving frugivores, freed from competition, eat fruit from fewer plant species. In Tonga, the insular flying fox — a bat species whose numbers are declining there — now rarely pick fruit from a tree then carry it elsewhere to eat, McConkey says. They just feed happily in the fruiting tree, dropping the seeds below. “When you’ve got a few bats, they don’t fight — and you’ve got no seed dispersal,” she says. “If there aren’t enough bats, almost nothing moves.”

Habitat fragmentation is a further problem, says Dov Sax, a conservation biologist at Brown University. “Much of Europe is in agricultural fields. And the same is true for much of the middle of the US,” he says. “That creates a huge barrier to dispersal.”

In so many ways, the world is now radically different from how it was during previous periods of climate change, Sax adds. “In North America and the UK, none of us grew up with elephants roaming the landscape, or giant sloths or lots of bison,” he says. “It’s easy to forget that that was the situation for millions of years, and that through all the previous episodes of climate change, those mammals were available to move seeds.”

Sax does note one significant uncertainty in forecasting how much plants must migrate to survive global heating. It’s possible, he says, that they have more built-in flexibility than assumed to deal with conditions different to those within their historical ranges. Still, there is widespread evidence that plant and animal ranges really are shifting. Parts of the Arctic tree line are moving towards the north pole by 40 meters a year or more; the US Environmental Protection Agency says ranges of North American species have moved north by an average of 16.9 kilometers a decade since the 1970s; and across the world plants are shifting to higher, cooler altitudes, including alpine species that have ascended hundreds of meters up the Himalayas and the Hengduan mountains.

What seed ecologists must do next is directly show if and how animals are facilitating — or preventing with their absence — such movements. They also need to learn how new communities function when novel plants join ones that already live at higher latitudes or altitudes, creating new combinations of species. Fricke’s modeling, supported by real-world data on existing introduced plant species, suggests that when fruiting plants move to new habitats, most of them will have their seed-dispersal needs met by local fruit-eating animals. But nobody knows for sure.

The answers have important implications for conservation (see sidebar). But for these issues to gain traction, the crucial role of animals in dispersing seeds needs far more appreciation among the public and from conservation policymakers, says Rogers.

Certainly, pollination by bees and other insects is now a flagship conservation issue. Maybe that’s unsurprising, since some 75 percent of human crops depend on animal-mediated pollination, whereas seed dispersal is primarily an issue for wild plants. But perhaps it’s also easier to turn bees flitting from flower to flower into icons of environmentalism than it is to celebrate thrushes or bears eating berries then defecating the seeds.

Nevertheless, seed dispersal is an essential ecological function, stresses Rogers. For wild plants, she adds — and therefore, the health of global ecosystems — the message is quite simple: “You can have all the pollination you want. But if it doesn’t get dispersed, it’s not going to succeed.”

Bridging national service and public health, the initiative supports a diverse group of early career professionals working to address today’s public health challenges in a range of roles, including:

Bridging national service and public health, the initiative supports a diverse group of early career professionals working to address today’s public health challenges in a range of roles, including: